In 1997, more than a quarter-century before John Z. Kiss would come to Melbourne as Florida Tech’s new provost and senior vice president for academic affairs, the soft-spoken space biologist and passionate space fan found himself at a crowded restaurant table at Cocoa Beach’s iconic Atlantic Ocean pier.

It may as well have been heaven.

Kiss, then an assistant professor at Miami University, and the school’s vice president for research – a physicist and fan of both NASA and Kiss’s research – had come from their Oxford, Ohio, campus. Kiss was assisting with training two mission specialists on his project ahead of space shuttle mission STS-84 that was headed to the Mir space station.

Jean-Francois Clervoy and Elena Kondakova were set to work on his experiment, which would document the effects of the space environment on the biological systems of plants. As they wrapped up their day, Kiss asked Clervoy if he’d be interested in getting dinner. The French astronaut said he would be and would call after going to the gym.

“My vice president is like, ‘He’s never going to call you. He’s just being nice,’” Kiss recalls.

At 8 p.m. the phone rings. It’s Clervoy. He tells Kiss that he’s ready to go. That in fact “we” are ready to go.

“Do you mind if we bring the entire crew?”

Pause.

“I said, ‘Oh no, no. That’s fine,” Kiss says.

And that’s how the astronaut aficionado found himself surrounded by six astronauts, including the female pioneers Eileen Collins (the first American woman to command a shuttle mission) and Kondakova, the hero of the Soviet Union who held the record in that country for time in space by a woman.

“The one time I don’t have a camera, I had three astronauts on my left and three on my right,” Kiss says.

As Kiss embarks on his own journey at Florida Tech, he brings wonder about space and a hearty appreciation of its cultural trappings, from mugs to autographed astronaut pictures (he has many), that have only grown since that memorable meal. (He also has an asteroid named after him.)

He brings a scientist’s curiosity that also has flourished since then, with the recognition, funding and awards that follow.

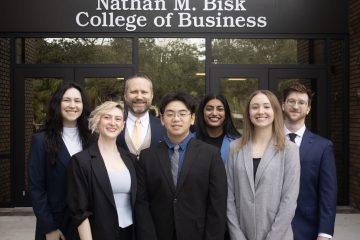

And he brings a fondness for the teacher-scholar model – which values experiential learning for students and a balance of research and teaching for faculty – that has allowed him to remain both an active space biologist with ongoing research and an impactful administrator. “It’s one of my favorite phrases,” Kiss says of ‘teacher-scholar.’ “I think it has been really important in my career, and I think it fits in really well with what’s going on at Florida Tech.”

An Influential Professor

Like many kids, a young John Z. Kiss was interested in space. That interest blossomed during one of the early space industry’s crowning moments: the Apollo 11 Moon landing televised on July 20, 1969.

“The landing on the moon was a phenomenal technological achievement,” he said. “They were pushing the limits of computer power to land Apollo, and they also took risks that we’re too risk averse to take now.”

That interest remained, but as he worked toward his undergraduate biology degree at Georgetown, a new one was on the horizon. He had to do a research project to graduate and, working with a professor who was a plant biologist, Kiss ended up doing two different ones, both plant-related.

“I decided after I worked with him for a few years that I wanted to go to grad school,” Kiss said. He did so at Rutgers, where he would continue his interest in plants and earn a Ph.D. in botany and plant physiology.

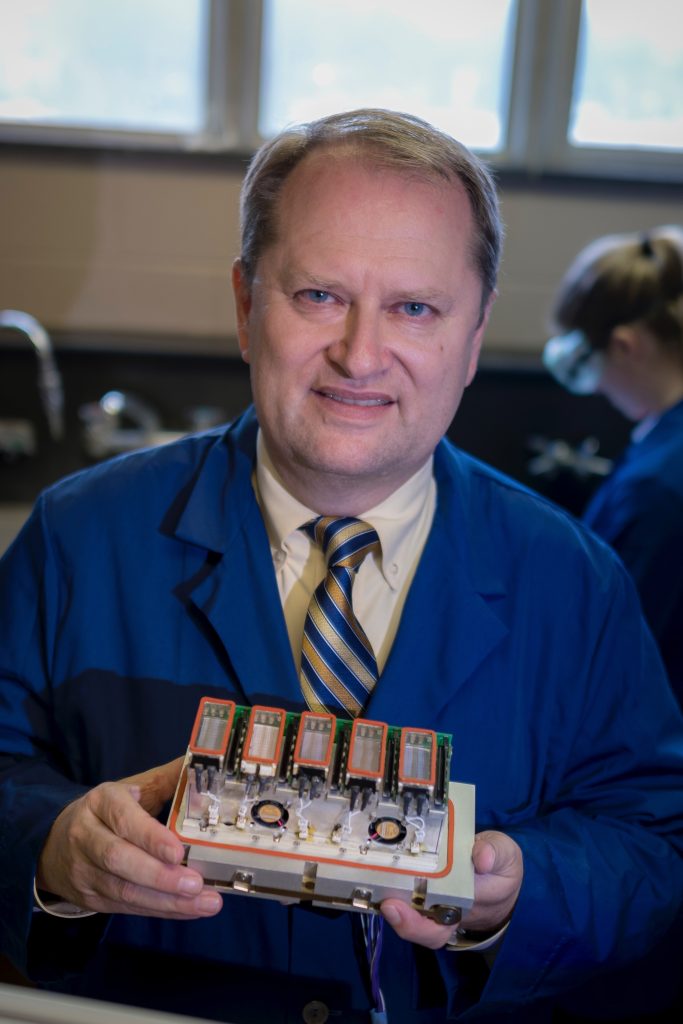

The other cornerstone of Kiss’s academic career came to the fore as he served as a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Plant Biology at Ohio State University in the late 1980s. The position offered NASA-funded, ground-based research into the structural and functional aspects of gravity perception in plants.

“Ever since then, I’ve worked with NASA on ground-based and space flight research,” Kiss said.

But even as he was learning science, he was, like the best scholars, also drawing other lessons from his experiences. His research projects at Georgetown showed the value of undergraduate research to help clarify a future focus. His work with that professor showed how much one could influence a student.

“I always go back to that concept with faculty because they can feel down at times about the state of things,” he said. He tells them, “’Take a step back. You’re doing research that is close to your heart and you could touch the lives of young people.’ It’s really a phenomenal thing. I was really fortunate to have that professor.”

Teacher-Scholar

Having conducted NASA-funded research at OSU, Kiss’s next job now had the agency in the title: NASA Research Associate. For a year he held that role at the University of Colorado. Then in 1991 he landed his first faculty role as an assistant professor in the biology department at Hofstra University.

Two years later, he arrived at Miami University in Ohio and went on to teach undergraduate and graduate courses in biology and botany at Miami University in Ohio for 19 years. It was during this time he had the fateful Florida dinner with the astronauts.

It was also during this time his first plant experiment for space, to study gravity perception, was carried by Space Shuttle Atlantis to the Mir space station.

This 1997 experiment and the seven other experiments for which Kiss would serve as principal investigator over the next 20 years would employ similar approaches as distilled in an article on Kiss from his previous employer, the University of North Carolina Greensboro: “plants ride into space on rockets and are then exposed to different environmental stimuli.”

From Miami University, where Kiss was honored multiple times including as Distinguished Scholar of the Graduate Faculty and Researcher of the Year, he went to the University of Mississippi in 2012 and then onto UNC Greensboro, where he remained until coming to Florida Tech in May 2024.

Kiss was doing more than excelling in the classroom over this time. He was increasingly involved in administrative matters. At Miami University he was chair of the botany department, a faculty advisor, a member of several councils and committees and, as his time there ended, a member of the search committee for the graduate dean/associate provost for research.

That must have provided instructive because he was hired at the University of Mississippi as dean of the graduate school, which offered 65 master’s degree programs, five specialist degree programs and 42 doctoral degree programs. It was his most prominent leadership role to date.

At least until four years later, in 2016, when he was named dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at UNC Greensboro. There he oversaw 20 academic departments and 420 total faculty teaching nearly 7,000 students. He also continued his research and teaching as a space biologist.

At UNC Greensboro, Kiss worked to hire excellent faculty who exemplified the teacher-scholar model and strengthened the research profile in the college, where external grants increased 150 percent during his tenure.

External funding went from $5 million annually when he started to $14 million when he left.

Kiss himself has served as principal investigator on grants from NASA, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health with a career total of $11 million.

Inclusive Approach

As a higher education leader who straddles the classroom and the board room, Kiss knows well the value of seeking input from stakeholders, and in particular, faculty.

“One common lament I’ve heard (in higher education) is people make these top-down decisions,” he says. “I like to get faculty input on a lot of things rather than just me saying, ‘Hey, guys. This is what we’re doing.’ I think faculty are more likely to like that approach.”

To that end, Kiss is working with Chief Research Officer Hamid Rassoul to revive the Research Council, which he believes can be an important nexus between university and faculty for research endeavors.

“That’s one thing I definitely learned as dean: if you want to get something done, you have to work with the faculty,” he said.

Kiss is also excited about growing external research finding at Florida Tech and investing in new faculty. Additional university support will be key.

“That was how I increased funding was to really help with the infrastructure of the research office, and I invested in new faculty. Those are the two things.”

Speaking of research, Kiss has decades of research experience with NASA, the European Space Agency and several private companies, including SpaceX. He is impressed by Florida Tech’s ongoing research but believes it can grow.

“I know we do things with these companies, but I really would like to expand both space research and the research with NASA, international partners of NASA and some of the aerospace companies,” he said.

John Z. Kiss On…

Favorite Space Book: Endurance: A Year in Space, A Lifetime of Discovery by Scott Kelly, the distinguished shuttle astronaut and engineer.

Top Three Values as Provost: Teacher-scholar model; transparency; student success.

Resilience And Failure: “You can talk about, ‘Oh, John Kiss, you got these awards, these publications and grants.’ But I’ve applied for grants and didn’t get them. I applied as an assistant professor for faculty jobs and didn’t get them. You don’t generally talk about that, but I think students need to hear it. You shouldn’t be embarrassed. That’s part of the process.”

Going To Mars: “We can build the big rockets. But the questions to go to Mars are all biological. Not just plant biology, but what are the effects of the high radiation on humans? What are the effects of microgravity and partial gravity on human physiology? How are we going to grow plants on Mars?”

This piece was featured in the fall 2024 edition of Florida Tech Magazine.