By Erin Peterson

As humanity sets its sights on Mars, scientists are hungry to answer an essential question: How will our interplanetary travelers eat?

Student and faculty experts at Florida Tech suggest that learning to cultivate crops in regolith—the dusty, poisonous substance that covers the Martian surface—might be a key to feeding future explorers.

NASA predicts it will send its first astronauts to Mars in the 2030s. SpaceX’s Elon Musk dreams of creating a self-sustaining settlement on the red planet by 2050. And research stations and habitat prototypes are already being tested in remote areas of Earth to simulate what life might be like for these intrepid explorers.

There will be plenty of challenges facing these adventurers, and a big one is what and how they’ll be able to eat.

While there are a range of options, if there is one thing that associate professor Andrew Palmer feels confident about, it is this: Man cannot live on freeze-dried astronaut ice cream alone.

“There are some [experts] who think we can send prepackaged foods to Mars for [astronauts] to live off of, but it’s a very limited diet, and it’s not that healthy,” he says.

One potential, if complicated, solution is growing food inside a biohabitat using Martian regolith—the gritty material that blankets the planet.

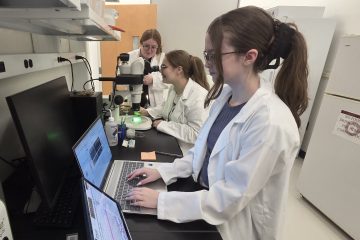

It’s a tall order. Regolith lacks nutrients and is laced with toxic chemicals. Still, many researchers at Florida Tech see potential in coaxing life from Martian terrain. Palmer is helping lead the charge not just at Florida Tech, but nationally, where the university has attracted significant notice from NASA, corporations and other schools advancing space-linked research.

“We have the distinction of being a very precise lab—we think about the physical and chemical properties, the mineralogy and the nature of the substrate,” Palmer says, listing off some of the lab’s strengths. “We take a very technical view of the subject, and we’re at the [cutting-] edge of a growing field,” he says.

In the pages that follow, we look at their efforts to turn barren land into a fertile ground—and build a foundation for a self-sustaining future on Mars.

First Thing’s First: Get to Know Regolith

Regolith is often compared to soil, but the two are (quite literally) worlds apart.

Soil is a living ecosystem with microbes, organic matter and a structure that supports water, air and nutrient flow; Mars regolith is a mix of rock and dust, containing lots of toxic materials and no life at all.

We don’t have access to real regolith.

Mars rovers haven’t brought any regolith home with them, but thanks to gas chromatography, mass spectrometry and laser spectrometry analysis, scientists do have a detailed sense of its composition. That said, Mars regolith is not uniform.

“If you go from Florida to California, the soil varies significantly,” says Toufiq Reza. “On Mars, the regolith varies as well.”

Florida Tech does much of its testing on a lab-developed regolith simulant known as “Mars Global.”

Spending on Simulant

Mars regolith simulant variations cost between $30 and $50 per kilogram; Florida Tech spends about $3,000 on simulant for its research annually.

To Use Regolith for Extraterrestrial Agriculture, We’ll Have to …

Strip out the toxic chemicals

ESPECIALLY PERCHLORATE …

Perchlorate is by far the biggest baddie as we think about growing food on Mars. It’s so dangerous that Earth-manufactured simulants do not contain it because it is linked to cognitive impairment, respiratory problems and a range of different cancers. (Researchers who want to study it in the simulant must add it in separately under highly controlled conditions.) In a collaboration with researchers from Arizona State University, Frannie Edmonson ’23 is studying if plants can be grown successfully in regolith that has been infused with perchlorates and then treated to neutralize them.

“It’s almost like we’re domesticating it,” says Edmonson. “[Regolith] is really wild and elemental, and we’re trying to get it into a more familiar form.”

… AS WELL AS ZINC, CHROMIUM AND MANGANESE (AMONG OTHER THINGS)

Emily Soucy ’25 has found one offbeat solution: bladderworts, carnivorous plants that can grow in nitrogen-poor environments and absorb metals into their tissues.

Introduce Chemicals That Plants Will Need to Thrive

LIKE NITROGEN …

One possible option to introduce nitrogen into the regolith is through cyanobacteria—an organism known as an “extremophile” that can thrive even in harsh environments. In her experiments growing cyanobacteria in simulant, Haley Murphy ’24 found that the organism could likely convert Mars’ atmospheric nitrogen into a usable form for agricultural life.

“On Earth, we use these species of cyanobacteria to generate fertilizer from materials in the surrounding environment,” she says. “If we can replicate this on the moon and Mars, it will limit the amount of materials we have to ship and make extraterrestrial farming more feasible.”

… AND CARBON

To introduce carbon into regolith, Toufiq Reza and Robert Cheatham ’24 are experimenting with biochar, a carbon-rich material that could be developed by heating organic material—like the inedible parts of plants—at temperatures of up to 600 degrees Celsius. Biochar has an added benefit, says Reza: It can help with water retention, another challenge of regolith.

Make the Regolith Behave Like Soil

Regolith is typically light and dusty—but once water is added, its texture and cohesion is similar to clay. To support plant growth, the mix needs to be well-aerated so air, water and nutrients can circulate. Trent Causey ’25 has found that ground-up peanut shells—fibrous and slow to degrade—could be mixed into regolith to support a soil-like structure. Peanuts, he says, offer a tantalizing twofer: The hardy crop, which grows in some regolith simulants, would also be a good source of protein and fat for Mars residents.

Take a DIY Approach

Why such a big focus on creating soil from scratch? Experts estimate that it costs about $100,000 to bring a single pound of material to Mars, so they’re focused on in-situ resource utilization—developing and using materials on-site, rather than bringing them from Earth. Hayley Ernest ’22, ’25 M.S., has conducted research zeroing in on the potential of clover, which can be grown in regolith and paired with its symbiotic bacteria, rhizobia, to draw nitrogen from the atmosphere and convert it into nutrients. Once dehydrated and tilled back into the soil, the clover enriches the regolith, creating a stronger, more fertile substrate for future growth. It’s a tiny system that can be expanded: The rhizobia bacteria can be transported to Mars in a small, self-watering cord. That’s led Ernest and her labmates to suggest that astronauts could potentially “take a pack of clover seed and a shoelace full of bacteria to Mars, and you will have dirt.”

So, Looking at the Big Picture …

The first crops for human consumption will likely be quick to grow, easy to manage and entirely edible—think lettuce and basil.

Could Ketchup be on the menu?

As part of a two-year collaboration starting in 2019, Palmer worked with Heinz to grow some 450 ketchup tomato plants in regolith simulant. The tomatoes were transformed into a limited-run prototype “Marz Edition” ketchup.

Some Earth-based foods might never appear on the red planet.

“Agricultural economics look very different on Mars,” Palmer says. Water-intensive crops, like almonds and acai berries, are likely a no-go.

Cultivating food on Mars will help it feel like home.

It’s one thing to travel to a place and eat prepackaged food. It’s another to literally put down roots and grow your own, Palmer says.

“I think we’ll feel more like we’re vacationing—or just on Mars for work—until we’re growing food there.”

We can apply the lessons from this research to our home planet.

The work that Florida Tech researchers have done has plenty of applications closer to home: It can help communities with poor soil conditions or in extreme environments increase their agricultural yields. It can also help remediate soil around mines or industrial areas.

“We are taking the most challenging scenario and trying to solve that one,” Reza says of their work on Martian regolith. “If we can solve that one, everything else will be easier. We’ll learn so many things along the way.”

Could Matt Damon’s Mark Watney really have grown potatoes in the regolith he modified, as he did in the Oscar-nominated film “The Martian”?

Palmer has his doubts about the process shown in the movie (perchlorates are one reason), but he holds his fire.

“I love ‘The Martian’ because it’s inspirational,” he says. “It really provides people an opportunity to think about what could be.”

This piece was featured in the fall 2025 edition of Florida Tech Magazine.