Engineering Students Dive into Water Projects: Attracted by Hands-on, Real-world Experiences

Assembly complete. Ready to deploy.

On a sunny March day, sitting outside the Link Building, home of the Department of Marine and Environmental Systems, Hunter Brown’s eyes light up when he talks about the project that will earn him his ocean engineering master’s degree. The underwater inspection and surveillance vehicle, he says, has anti-terrorism potential.

Hunter Brown reviews plans for the underwater inspection and surveillance vehicle.

Brown is like most men and women attracted to Florida Tech for ocean engineering—they have a passion for going to the beach, for surfing, scuba or both. They think it’s fun to tinker with things mechanical and challenging to conceptualize and design.

An integrated ocean engineering curriculum and hands-on, real-world opportunities draw the undergraduates. Master’s and doctoral students enroll because the university offers one of the country’s few graduate programs in the discipline. And because, like Brown, they can dive into vehicle projects that combine their most intense interests.

Brown, a scuba diver with a technical rating, has finished the software, tether and interface, as well as the design of the three-foot-long, unmanned project. Now he’s tackling the vision component.

“It will have two cameras, one on the front and one on the side,” he says. “It will ‘fly’ underwater, inspecting a pipeline, for example, with the side camera, and ‘look’ forward for obstructions.” Potentially applicable for homeland security, the vehicle could locate packages of drugs or mines attached to the undersides of vessels.

The program combines many of his interests. He’s capitalizing on a bachelor’s degree in applied mathematics, an interest in the underwater world and a summer undergraduate experience where he developed a machine vision project.

Although the vehicle may not be a finished product when Brown graduates this summer—lacking its structural housing—he will be able to demonstrate its capabilities in a Florida Tech pool. Then, another student can complete the project for graduate credit, maybe adding a robotic arm or some sensors, too.

“Many of the projects become refined and completed over the years by a series of students,” says Dr. Stephen Wood, assistant professor of ocean engineering and Brown’s faculty adviser. Wood, who is also coordinator of the Florida Tech Underwater Technologies Laboratory, sits today in this Frueauff Building lab, surrounded by projects in various states of completion.

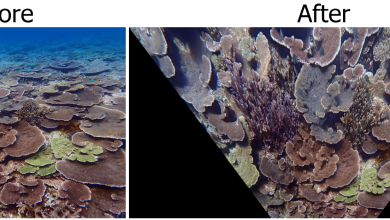

The MARC-1 (Modular Amphibious Research Crawler) is an example of a project shaped by many hands, as students have tinkered with it for their design project over several years. All undergraduate engineering students must complete a design project in order to graduate.

“The remotely operated MARC-1 began in spring 1999. The first year they built the basics, the second year the instrumentation, motor housings and extension pole went on,” says Wood. “When the third year students grappled with it, they threw out much of what was already done and the team started over.

“It was a lot of trial and error. Sometimes failure is better than immediate success,” says Wood.

Wood published an article on the three-wheeled vehicle in the February 2006 issue of the journal, Sea Technology, and has fielded a few inquiries about its commercial use, including one from a clammer.

Designed to operate underwater in the surf zone, the vehicle can reduce or eliminate the need for divers. Today the remote-controlled MARC-1 is 95 percent finished. Wood expects to see it used in physical oceanography classes for coastal processes, beach profile surveying and for scientific data collection.

This year 15 ocean engineering undergraduate students displayed their projects in an April design showcase. One team presented an autonomous mobile buoy to monitor coastal and lagoon areas and collect data on ecosystems; another exhibited a glider AUV, which will extract biological samples from the water column and take photos; another group showed off a powered hydrofoil boat; and a team adapted a previous design team boat project into a displacement hull ship. A displacement hull carries a heavier load and travels further on less fuel.

“Every senior design project is practical. They can be used later by students and faculty in research,” says Wood.

Guiding students on these and similar projects keeps Wood plenty busy.

“It’s so gratifying to see a student go from start to finish on a project,” says Wood. “This university allows the students to tackle a variety of underwater projects. Our ocean engineering program offers underwater technologies, naval architecture, instrumentation, coastal processes, bio-fouling and corrosion. We have it all.”

Karen Rhine