Secret History: “Bombs Away”—The Great Pingpong Ball Shenanigan

The History of Florida Tech's First Homecoming Celebrations

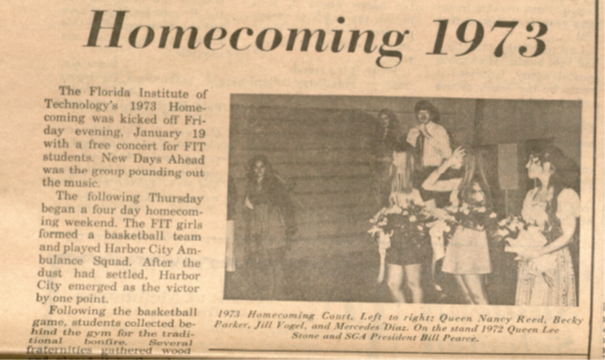

Dateline: January 25, 1973

Florida Tech’s First Homecoming

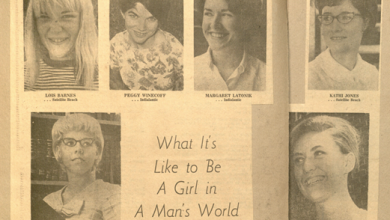

Florida Tech held its first homecoming in January 1972. The four-day event proved to be a debacle. There was little student interest in the festivities. The high point (or low point, depending on your perspective) came on the basketball court. The muscular “Knights of Pegasus” from Florida Technological University (today University of Central Florida or UCF) thrashed the diminutive Florida Tech Falcons[i] 125-66. Adding insult to ignominy, the scarcity of coeds at “Countdown College” led a group of cigar-smoking, would-be engineers to dress-up in cheerleader costumes. A handful of crestfallen Falcons lingered in the Percy Hedgecock[ii] Gymnasium for the post-game dance featuring a local band named Skunk Junction.

The Genesis of ‘The Great Mystery Contest’

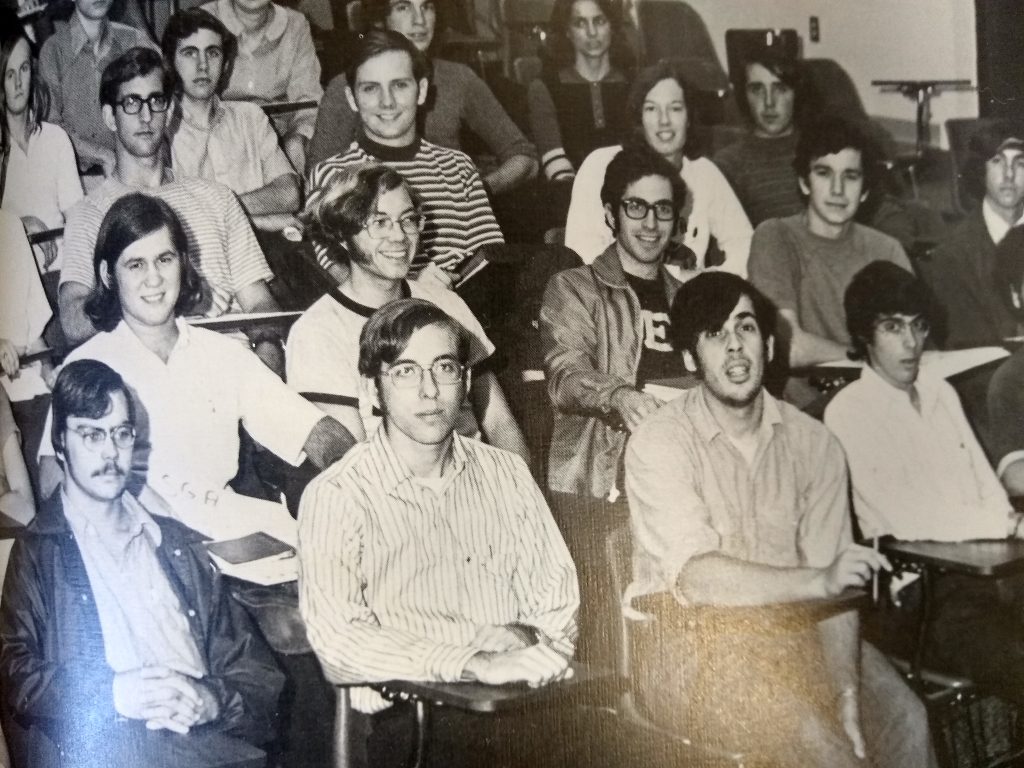

Stu Mendelsohn ’74, ’75 M.S., then an ocean engineering junior, thought Florida Tech’s Homecoming stunk. Years later, Mendelsohn remembered a series of late-night bull sessions following the fiasco with Bill Pearce ’73, ’74 M.S. Pearce, Florida Tech’s Student Government Association (SGA) president at the time, and Mendelsohn, then SGA vice president, were determined to increase student participation in the 1973 homecoming. The problem was motivating the students. In December 1972, Mendelsohn and Pearce hatched the idea of organizing a “Great Mystery Contest.”

What could go wrong?

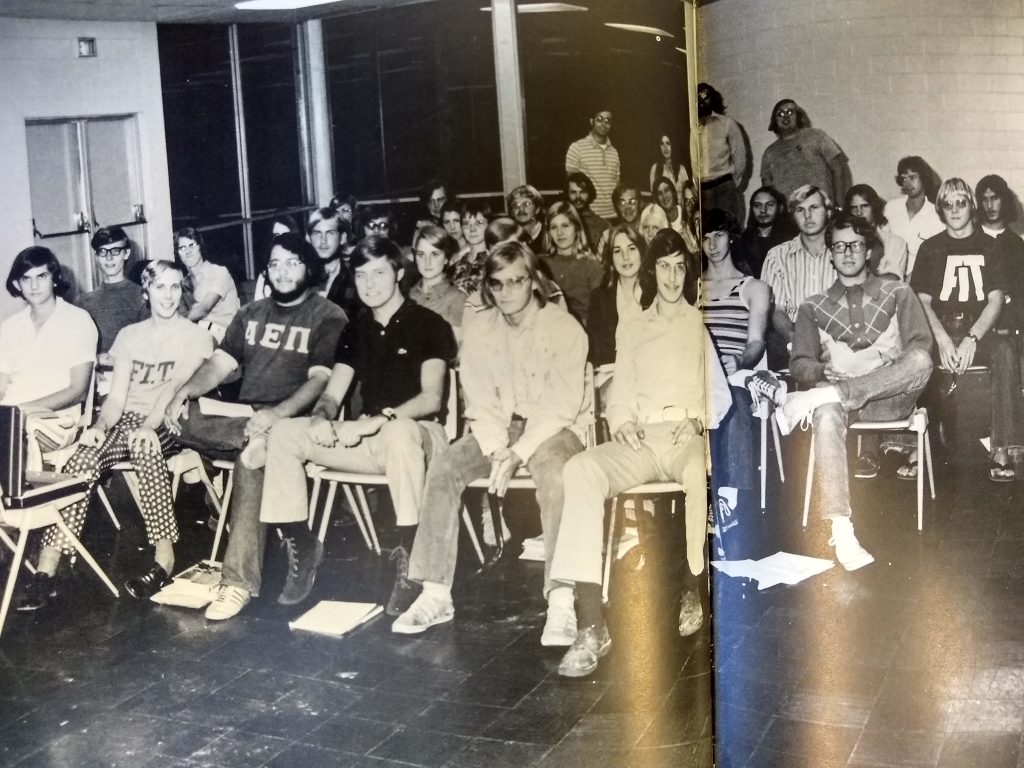

“What could go wrong?” Mendelsohn recalls asking William Rose, then Florida Tech’s dean of students, “we’re a technical school.” Rose’s eyebrows rose as Mendelsohn outlined the plan. The idea was to tell students that there would be a bonfire behind the Hedgecock Gym following the Homecoming basketball game. As the fire blazed, students would be instructed to go to the athletic field west of the gym with flashlights where there would be an opportunity to win valuable prizes. At a predetermined time, an F.I.T. Aviation plane would fly over the athletic field, dropping hundreds of numbered pingpong balls. The students who found the three lowest-numbered pingpong balls would win their choice of an eight-track stereo, a magnum of champagne or a $15 cash prize.

Rick Hansen, an F.I.T. Aviation student, would fly the plane. Mendelsohn and Pearce had checked with the local Federal Aviation Administration, which had no objections as long as the plane remained above 1,000 feet. The trio claimed to have thought of everything down to designing a device that would rest on the aircraft’s wing. When the mechanism’s handle was pulled, a cascade of pingpong balls would drop from the plane.

“What could go wrong?”

Plans Go Awry

On Thursday, January 25, 1973, the four-day celebration of Florida Tech’s second Homecoming kicked off with a basketball game between the all-volunteer Harbor City Ambulance Squad and a coed Florida Tech team.

Behind the Hedgecock Gym, Florida Tech fraternity brothers liberally doused a large pile of wood they had collected with 15 gallons of kerosene. Unbeknownst to Pearce and Mendelsohn, who were to light the fire, a prankster had hidden multiple packs of firecrackers in the pile. When the SGA president and his VP lit the fire, the firecrackers went off in staccato blasts sounding like a .50-caliber machine gun.

With the bonfire blazing behind him, Mendelsohn used a bullhorn to announce that the “Great Mystery Contest” was about to begin. The students dashed to the athletic field. With the sound of the airplane’s motor growing louder, Mendelsohn told the gaggle of students to direct their flashlights skyward. The single-engine plane, however, was coming in far lower than the designated 1,000 feet. Clearly, something had gone wrong. Later, Hansen told Mendelsohn that the handle on the pingpong ball drop mechanism had broken, and the contrivance’s failure caused a delay in the drop. As Hansen struggled to release the mechanism, the plane lost altitude, passing at treetop level over the athletic field and skirting Crawford Science Building. When Hansen finally managed to release the pingpong balls, the plane had crossed Country Club Road, and a barrage of pingpong balls fell on the homes west in the University Estates housing development.

The Fray Begins

When the students saw what had happened, someone yelled, “Over here!” and a mad rush to the neighboring housing development started. The balls were in driveways, bushes, yards and even on roofs. People with flashlights combed the area, finding pingpong balls everywhere. Several sleepy neighbors woke up, saw a fire in the background and must have thought a riot was in progress. A .45-caliber pistol and a shotgun were reportedly seen.[iii] Mendelsohn remembers a man coming out with a gun.

“It was not a good situation,” he said. He decided to leave when he saw the first of the Melbourne Police cars speeding down Country Club Road.

The Reckoning

The next morning, Mendelsohn received a cryptic phone call from Dean Rose, ordering him to be in his office in 10 minutes.

“Oh, I’m in trouble now,” Mendelsohn recalled thinking as he made his way there.

“Tell me,” Rose started, “what happened last night?”

Mendelsohn explained the series of mishaps that led up to Hansen’s “bombing” the school’s neighbors. Silence ensued. After what seemed an eternity, Rose broke into laughter. It was Homecoming weekend. No one should get bent out of shape over a few pingpong balls, he said. Ron Hix, who had won the eight-track stereo with pingpong ball No. 11, agreed.

A Pingpong Ball Presidency

A few weeks later, Mendelsohn was elected SGA president. His campaign posters showed a plane with pingpong balls falling from the sky with the slogan “Vote for Stu.” When the votes were tallied, Mendelsohn won the presidency with an 18-vote majority. “Landslide Stu” credits the “pingpong” balls falling from heaven for his victory.

Homecoming at Florida Tech

In the 50 years since the university’s first Homecoming, much has changed at Florida Tech. Some things, however, have remained constant.

When students and faculty see something that “stinks,” they do something about it. That was the genesis of the “Great Mystery Contest.”

Eleven years later, Florida Tech students invited Ralph Nader[iv], the political activist known for his advocacy of consumer protection and environmentalism, to campus as part of the 1983 Homecoming. No pingpong balls fell from the sky, but Nader’s Homecoming message to students rings as true today as it did forty years ago:

“If you really want to develop a full-dimensional engineering education, you should be asking not only technical questions, but questions of justice and injustice, health and safety. … You are the trustees of millions of silent Americans who are relying on [you].” That’s a homecoming theme worth embracing both then and now.

Go Panthers!

Ad Astra per Scientiam.

[i] In December 1970, The Crimson reporter Rich McEnergy lamented the lack of a school mascot. McEnergy wrote, “Florida Tech Basketball team still has no name. Woe is them. They also have no wins. Double woe.” In the 1960s, Florida Tech’s athletic teams were known as the “Engineers.” Two months later, The Crimson sought to remedy the situation, announcing a “Name the Team Contest” to identify the school’s mascot. The name “Falcons” was chosen. The Falcons, however, never caught on. During the next four years, news reports described Florida Tech’s teams as both Falcons and Engineers. In 1975, the name Engineers returned as Florida Tech’s official talisman. Eight years later in 1983, the university’s Athletic Advisory Council voted to adopt “Panther” as the university’s official mascot. Bill Jurgens, then Florida Tech athletic director, explained, “We’re not saying we’re not engineers. We just adopted a mascot.”

[ii] Percy Hedgecock (1916-1987) was the co-founder of Satellite Beach, Florida, and an early supporter of Florida Tech. In July 1968, construction began on Florida Tech’s first gymnasium. The building cost $130,000. In 1986, the gymnasium was named in honor of Hedgecock. In 2000, ground was broken on the $6.6 million Charles and Ruth Clemente for Sports and Recreation on the site of the Hedgecock Gymnasium.

[iii] Homecoming 1973, The Crimson, February 5, 1973, page 1

[iv] In 1965, Ralph Nader published the bestseller Unsafe at Any Speed, an exposé on the American automobile industry. Nader would go on to lead the anti-nuclear power movement, serve as the Green Party’s presidential candidate and be the subject of the 2006 documentary, An Unreasonable Man.