The Secret History of Armadillos with Leprosy

Dateline: Florida Tech 1983

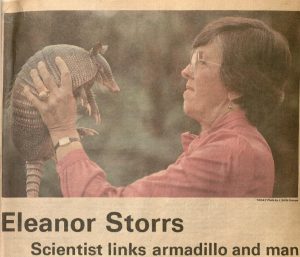

The nine-banded, long nosed armadillo paused when it sensed the movement. Eleanor Storrs and James MacArthur froze. This was the critical moment. Since coming to F.I.T. in 1978, Storrs, had captured hundreds of armadillos in the course of assembling the world’s largest colony of Dasypus novemcinctus (armadillos). This colony was the critical element in a leprosy research project sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Storrs, a research biologist at F.I.T.’s Medical Research Institute (MRI) had attracted international attention. An article published in 1982 in National Geographic had sparked the interest of the producer for a television program called the Scheme of Things which aired on the Disney Network. A year later in March 1983, Disney Studios dispatched a film crew and the program’s moderator, James MacArthur, to Countdown College. Two days were budgeted for the shoot. On the first day the director wanted to film Storrs and MacArthur catching an armadillo in the wild. On the second day the director planned to bring the shoot to Storrs’ laboratory at F.I.T.

Eleanor Storrs became one of the world’s leading experts on armadillos by a circuitous path. Born in 1926, Storrs graduated from the University of Connecticut in 1948 with a degree in botany. A decade later she earned a master’s degree from NYU. During these years she met her husband, Harry Burchfield, a renowned biochemist, who worked at the Boyce Thompson Institute in Yonkers, New York. With her husband’s encouragement, Storrs, a mother of two small children, decided to pursue a Ph.D. at the University of Texas. A few weeks after her 41st birthday, she was awarded her doctorate with a dissertation on the North American armadillo, Dasypus novemcinctus.

Storrs became fascinated with armadillos early in her doctoral studies. This small, armored, none-too-clever animal spends its days sleeping and rooting for insects. When caught off guard, it has the tendency of jumping which often leads to armadillo fatalities caused by passing cars. In Central and South America, armadillos are considered a gastronomic treat*. It was, however, the armadillos’ extraordinary reproductive practices which drew Storrs’ attention. Armadillos are unique in their propensity to give birth to quadruplets. Moreover, pregnant armadillos have the ability to delay giving birth when held in captivity. Storrs dissertation, Individuality in Monozygotic Quadruplets of the Armadillo,” offered a detailed examination of the animal’s exotic reproductive repertoire.

Chance plays a crucial role in most human endeavors. After completing her doctorate, Storrs and her husband joined the Gulf South Research Institute in New Iberia, Louisiana. In 1971, Storrs happened to overhear the conversation of a group of leprosy researchers working at a near-by U.S. Public Health Service Hospital. They were lamenting the absence of any animal model that could be used for leprosy studies. Storrs broke into their conversation. “I asked them,” she recalled, “if anybody had ever tried to inoculate an armadillo with leprosy because their body temperature is 90 to 92 degrees. They laughed at me. I mean it must have sounded strange — an armadillo.”

Stranger things do happen. In the weeks following that conversation, Storrs discovered that one of the wild armadillos she had captured in Louisiana had leprosy. Further research demonstrated that armadillo blood which had been frozen a decade earlier contained evidence of the bacteria. Storrs became convinced that armadillos do develop leprosy and was an ideal animal source for tissue studies of Mycobacterium leprae, the bacillus that causes leprosy.

Leprosy, or more properly, Hansen’s Disease, is one of the most misunderstood of human diseases. Once thought to be highly contagious, lepers were scorned and driven from their homes. “Anyone with such a defiling disease,” Moses wrote in Leviticus (13:45), “must wear torn clothes, let their hair be unkempt, cover the lower part of their face and cry out, ‘Unclean! Unclean!.’” Today it is known that the disease is caused by a bacillus which attacks nerves in cooler body extremities such as in arms, legs, and hands. In humans, the bacillus can remain dormant for a decade. Untreated, Hansen’s Disease can lead to terrible disfigurement, multiple amputations, and death caused by secondary infections. Fortunately, the great majority of humans (estimated to be 95%) are resistant to the bacteria. For those millions who are not, contracting the disease is horrific.

Between 1971 and 1978 Eleanor Storrs fought against an entrenched medical establishment which discounted her experiments. What did a woman, let alone a biologist who studied armadillos’ procreative peculiarities, know about Hansen’s Disease? “This is [was] a very closed group of people,” Storrs explained. “they were disturbed and upset that something was jeopardizing their program. They didn’t like our research.” Storrs and her husband soldiered on. In 1974, their path breaking work was recognized in a lead article in the prestigious journal Science. Subsequently, the WHO and NIH awarded Storrs a series of contracts to provide armadillo tissue with leprosy for studies seeking for a vaccine against the disease.

Four years later Storrs accepted a research professorship at Countdown College. Storrs brought her armadillo research on leprosy to Florida Tech’s Medical Research Institute (MRI). The MRI was the brainchild of Ronald Jones, a garrulous University of Georgia educated biologist who was working at the University of Michigan. In 1971, four days after his marriage, Jones and his wife, Alice, who had a Ph.D. in immunology arrived in Melbourne. John Thomas, a chemist, and his wife, Betty, joined the Joneses in launching Countdown College’s foray into biomedical research.

The MRI was housed in a ramshackle building three miles west of the Country Club campus on US 192 which Jerry Keuper had acquired from Cecil Platt, a local cattle baron. Jones envisioned the MRI as having a compliment of thirty researchers. That would have to wait. The immediate task facing the couples was refurbishing a vandalized, broken down building, clearing out the vermin that had taken up residence, and finding a roofer. Jones quickly learned that at Countdown College all things were possible so long as you went out and found the money to pay for it.

Jerry Keuper and John Miller had high hopes for MRI. Keuper believed Jones’ claim that he was close to discovering a vaccine for syphilis. “I think there is a real possibility,” Keuper exuded, “that in the years ahead he [Jones] will win a Nobel Prize for Medicine through his research and that of his colleagues.” Twelve months later, John Miller was equally effusive when he learned that Jones had secured a research grant for his quest for a syphilis vaccine. “I feel like I should be in the middle of a Chicago stadium surrounded by 100,000 people,” Miller exclaimed, “this is such an important announcement.” Years passed. Nothing came of Jones’ blustery claims for his syphilis initiative. The money dried up. Jones, however, remained undaunted. Between 1971 and 1987 Jones came up with an array exotic proposals ranging from a “telemetric” tooth implant, homeopathic treatments for a variety of life threatening diseases, to a scheme for utilizing ram semen in pursuit of a male contraceptive.

Convincing Eleanor Storrs to come to Florida Tech was Jones’ singular accomplishment. Storrs research brought credibility and international recognition to Countdown College’s fledgling medical research. Two years later, Storrs was joined by Arvind Dhople, a University of Bombay educated infectious disease expert. In India, Dhople had become absorbed in finding a vaccine and cure for leprosy. Storrs and Dhople formed a strong working relationship. During the next thirteen years they conducted a wide ranging series of experiments on leprosy and other infectious diseases. In 1993, Professor Storrs announced her retirement. Professor Dhople maintained the armadillo project for six months before arranging the program’s transfer to the National Hansen’s Disease Program based in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

By the time of her retirement, the MRI was long gone. In 1987, Lynn Weaver, shortly after becoming Florida Tech’s third president, closed the MRI. The disparity between Ron Jones claims and what the MRI had accomplished was apparent. Weaver encouraged Jones to seek new horizons for his unorthodox medical initiatives. Lynn Weaver, however, recognized the value of Eleanor Storrs and Arvind Dhople’s work. Both remained respected research professors in the biology department.

It was the nine-banded, long nosed, leprosy-bearing armadillo that brought Disney to Countdown College. This is why Eleanor Storrs and James MacArthur stood frozen in the Florida scrub on a March day in 1983. MacArthur, who played “Danno” in 259 episodes of the CBS television drama Hawaii Five-O, and Storrs held their breath as they waited for the armadillo to return to rooting for grubs. Patience was essential. Capturing an armadillo was never easy. Trapping an armadillo with an accompanying Disney film crew was daunting. It was over in an instant. Storrs had the armadillo by its tail. The animal was caught. Someone mumbled “Book’em, Danno.”**

At his retirement, Jerry Keuper paid tribute to Professor Storrs. In a newspaper interview, he described her work as one of Countdown College’s crown jewels. Looking back his career as a physicist and his twenty-eight years as the university’s president, Keuper declared with pride that “F.I.T. is the world’s largest supplier of leprosy-infected armadillo tissue. We ship it all over the world. We also supply sperm from sheep for reproductive biology all over the world.” Yes, Keuper added, “I’m proud of that.”

On May 20, 2018, Eleanor Storrs died after a brief illness. “Polly”, as her friends and colleagues called her, never lost her passion for science and love of armadillos. There was, she acknowledged a certain irony in the lodging of the world’s largest armadillo colony at Florida Tech. It is widely accepted that armadillos were introduced into Florida in the 1920s when four armadillos escaped from a roadside menagerie located in Cocoa, Florida.

Note: In 1983, the year of Disney’s visit, Countdown College adopted “The Panthers” as the university’s mascot. When the university launched its athletic program in 1964 the universities athletes were known as the battling “Engineers.” Professor Storrs and Dhople’s pioneering research lends credence to the notion that Countdown College’s unique élan might best be embodied in an armored rodent: Go Armadillos!

Ad Astra per Dasypus novemcinctus

*Aficionados claim it tastes like chicken.

**James MacArthur played Detective “Danny Williams” on Hawaii-Five O from 1969-1979. Typically, the program ended with Detective Captain Steve McGarrett’s (Jack Lord) catchphrase, “Book’em, Danno.”