Florida Tech Discovery Magazine, Spring 2019: Buggin’ Out

This article is featured in the Spring 2019 edition of Discovery, Florida Tech’s research magazine. To view this edition and Florida Tech’s archive, click here.

In comparative psychology research, species such as mice and pigeons are often used to learn about behavior and cognition. But given the requirements of veterinary care and storage and the ethical questions associated with the animals’ ultimate fate, a Florida Tech psychologist may have found a new option.

Just don’t step on it.

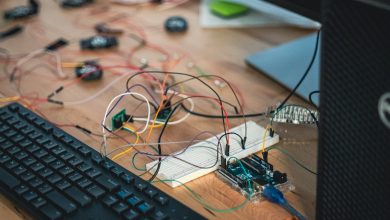

In her fall physiological psychology classes, Darby Proctor, assistant professor in the School of Psychology, introduced Blaberus discoidalis roaches to learn about neuroscience. The idea stemmed from a desire to provide an interactive experience for the students who are dealing with many complex concepts. Proctor uses equipment and electrodes that attach to a roach’s leg and can manipulate the neurons and electricity moving the limb. Students can then see the electrical activity via an iPad. This is the same process that works in humans.

“Now they get to see this thing happening, instead of me just telling them, ‘Really, there’s electricity in us,’” Proctor said.

The insects are an ethical and cost-effective learning alternative, and once their days participating in classroom are over, they can be housed in terrariums until the end of their lives.

Utilizing cockroaches as testing subjects is a new frontier that has a world of potential.

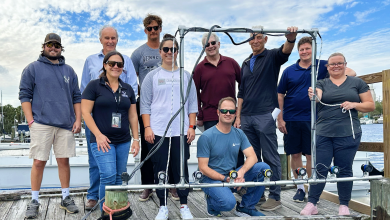

Proctor and Marshall Jones, director of College of Psychology and Liberal Arts Online Programs at Florida Tech, are working on a website that will serve as a source for other universities to implement roach experimental work in their undergraduate classes. However, with limited published research on roach experimentation, Florida Tech will also develop methodology to guide other classes so they can replicate the experiments in their classrooms.

In her classroom, Proctor teaches about action potential and neurons through the roaches in multiple ways. Utilizing a small, backpack-like attachment worn by the insects, students are able to deliver an electrical impulse to their antennae via Bluetooth, controlling the movement of the roach for a brief period. This is part of Proctor’s lessons used in a neuroprosthetics lab, showcasing muscle input used in robotic prosthetics for humans.

“That little electrical signal is mimicking an action potential, the electricity their neurons would fire,” Proctor said. “And because it’s such a simple model organism, we can hijack the neurons in their antennae, to mimic what they would feel if they ran into something. You’re basically tricking them and giving them the signal that they’ve run into something, so then they turn.”

Looking for multiple ways to utilize the roaches, Proctor also uses the insects in her animal behavior and comparative animal cognition classes. After going through the basic processes of cognition, Proctor lets the students design an experiment with the roaches to gain experience with the concepts.

Last semester, her students decided to create a traditional maze out of building bricks with a food goal at the end. Similar to experiments done with rats, the goal was to see if the roaches could learn the path to get to the food without too many mistakes, thus showcasing they had the basic cognitive process of long-term memory.

The test didn’t prove to be successful. The roaches didn’t seem to be motivated by food the same way rats or other mammals were; some even gave up in the middle of the maze. However, the maze gave way to another idea of testing, this time using a T-shaped maze. By simply giving the roaches a choice of going left or right, the students were able to analyze if the insects had another cognitive process, behavior lateralization.

These student-designed tests also showcased real-life issues in scientific testing.

“It’s really cool for the students to see that even though we as scientists want to do something and plan an experiment a certain way, sometimes we learn that doesn’t work. But every time you fail, you learn something new,” Proctor said.

Rob Hampton, a professor at Emory University’s Department of Psychology who has done work with cockroaches before, said the ability to do more studies with the roaches will benefit students at Florida Tech.

“It’s a great endeavor she’s started there, because it’s getting more and more complicated and less common to have laboratories where students actually get to do hands on work with any organisms,” Hampton said. “By getting things started with the cockroaches, it opens up a lot of opportunities.”

The Blaberus discoidalis species Proctor uses comes from the Caribbean and is noninvasive, slower than normal roaches and, at approximately 2 inches, large enough to handle for tests. They live for about two years and don’t fly, putting students more at ease.

The housing for the roaches is also important to Proctor. They live in a tank complete with their own 3-D printed-house, soil, water and yes, a running wheel to keep them stimulated. The roaches retired from experiments live out the rest of their lives in this habitat.

“Being in psychology, we always want to give our animals enrichment so they don’t get bored – if cockroaches can even get bored,” Proctor said.

Through his own work and an analysis of Proctor’s, Hampton he sees a bright future in the use of the insects.

“The cockroach is a relatively simple beast but there’s going to be all kinds of surprising things it will do and be capable of adapting to that they’re going to find by watching closely,” he said. “You get a bunch of students in there, they’re going to find things that no one has seen before.”

###