Secret History: The O.A. Holzer Medical Center

Dateline: 1981

The boots gave him away. “The Germans,” the train conductor quietly observed when he came to the young medical officer, “won’t fail to notice those army boots of yours.” Two weeks earlier the Nazis had seized control of Czechoslovakia. On March 15, 1939, a triumphant Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, and Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reich Security Service, arrived in Prague. A fortnight later, Oswald Holzer found himself on a train trying to pass unnoticed by the SS and Gestapo’s watchful eyes. Holzer remembered trying to conceal the tell-tale boots by pulling his pant legs down. “That won’t help,” the friendly conductor added, “You have to keep moving. There are Gestapo on the train…” (Schirm, 2019, p. 53)

Oswald Holzer Keep Moving

The past two weeks had been chaotic for the twenty-eight-year old, newly minted physician. The Czech army ceased to exist. Hitler’s henchmen began an active campaign of arrests and detention of what they deemed politically and racially suspect individuals. The situation was particularly dire for Holzer, a Jew and army officer, who had had the temerity to publicly criticize the Nazis thugs. “Keep moving” was the conductor’s imperative advice. During the next thirteen years, Holzer did “keep moving” making his way across Europe to Egypt, Yemen, Djibouti, Singapore, Shanghai, China’s interior, and on to Peru, and Ecuador, and, finally, in the summer of 1952 to Melbourne, Florida, where Holzer became the seventh doctor accredited to the Brevard Hospital Staff (Holmes Regional Medical Center). Until his death in 2000, Holzer and his wife Ruth Alice “Chick” Holzer found a safe haven “in a cozy Melbourne Beach house one block from the ocean —our only enemy the ubiquitous mosquito.” (Schirm, 2019, p. 286)

Oswald Holzer was a remarkable man. Like so many immigrants, Holzer felt a deep love for the country that had given him refuge. In the 1950s and 1960s, he served on innumerable city, county, and state commissions. He had a special passion for helping young people. That was undoubtedly one of the reasons why Holzer became friends with his Melbourne Beach neighbor Jerry Keuper. A graduate of Charles University in Prague, Holzer shared Keuper’s conviction that education held the key to a better future. China was another connection. Keuper had served as an intelligence officer in the Office of Strategic Studies (OSS) during World War II. The two men regaled one another (and whoever else would listen) with stories of their experiences in the Middle Kingdom. When Holzer told Keuper of his intention to retire, Keuper began his campaign to convince Holzer to become the head of the fledgling college’s student health center.

Keuper Meets with Students

The need for a campus student health center had surfaced in 1970. The initial “missilemen” (both men and women) who worked at the Cape who had formed the first cohort of Brevard Engineering College and Florida Tech students were covered by their employers’ health plans. Florida Tech had become a residential college by 1970. On January 27, 1970, Jerry Keuper held his annual meeting with student body. In his prepared remarks, Keuper announced plans for a new dormitory which would include a cafeteria (Evans Hall) and a “snack bar” that would be open “til one o’clock in the morning…so it will always be available for cokes and hot dogs.” Additional plans called for enhancing student services included a four-lane bowling alley, improvements in the gymnasium, and expanded parking.

At the end of his presentation, Keuper asked if there were any questions. “Is there any chance,” a student shouted, “of getting [a] campus health facility?” Keuper acknowledged that this was a growing concern. A recent flu epidemic had swept through the dormitories. Students complained that they were unable to find a doctor willing to treat them. “This is something,” Keuper declared, “that I’ve been concerned about recently with all this flu epidemic. Up until very recently we really haven’t had a pressing need for someone full time on campus such as a doctor or a nurse. But I think the time has come where we’ve got to give it very serious consideration. It might be that we should consider putting some sort of infirmary in the new building. Anyway, that’s a good point and we are going to have to do something about it very soon.” (Anonymous, February 10, 1970, p. 1)

The Holzers’ Gift to Florida Tech

Jerry Keuper’s use of the word “soon” is open to interpretation. Four years elapsed before the university was able to employ a full-time physician. In 1974, Oswald Holzer retired from his medical practice. In 1975, Holzer agreed to become Florida Tech’s unpaid medical director. During the next six years, Holzer, who was affectionally known as “Bubba,” organized the college’s nascent student health center. Seven years later, in June 1981, the ground was broken on the O.A. Holzer Student Health Center. The $65,000 facility which was located on the west side of Country Club Road was largely financed through the generosity of the Holzer family. (Anonymous, 1981)

Oswald Holzer continued to serve as the university’s medical director until the early 1990s. In 1984, Holzer and his wife returned to China where they had met in Beijing nearly forty years earlier. When they returned from China, Oswald and “Chick” Holzer chronicled their experiences in the inaugural lecture in the university’s Humanities Lecture Series in the pavilion of the newly opened Evans Library. As a memento of the conductor’s advice to “Keep Moving,” the Holzer’s presented the Evans Library with a Tang Dynasty relief of a horse that hangs in the library’s stairwell.

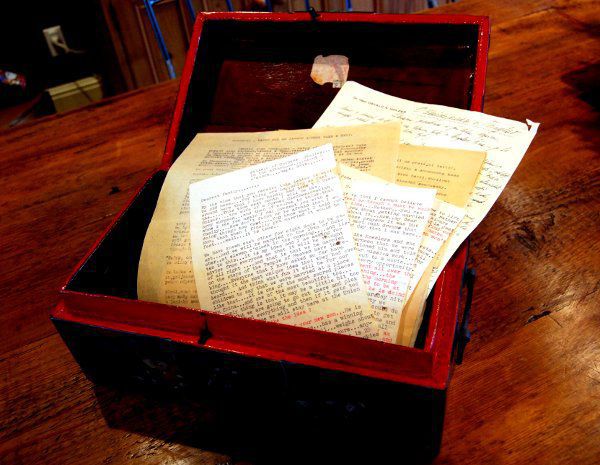

A Red Chinese Lacquered Box

Oswald Holzer died in 2000, two days after his beloved wife Chick’s passing. In the weeks following their passing, the Holzer’s children (Tom, Pat, and Joanie) began the process of sorting through their parents’ belongings. “My siblings and I reminisced,” Joanie Schirm recalled, “…until Pat brought us back to the task at hand. ‘Where do we start?’ ‘With the Chinese red lacquered boxes,’ Tom laughed.” The two boxes contained 400 letters that Oswald Holzer had kept chronicling the odyssey that brought him from a railway carriage in Europe to a “cozy home” in Melbourne Beach. In 2019, Potomac Books an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press published Joanie Schirm’s edition of these papers in My Dear Boy: A World War II Story of Escape, Exile, and Revelation.

The letters document moments of monumental pain and loss. And, yet, through all the suffering, Oswald Holzer remained hopeful that good could prevail. In 1945, Oswald Holzer learned that his parents had perished in the Holocaust. An aunt sent him a sealed envelope which contained his father’s final message. “My dear boy,” Arnost Holzer wrote, “you have always been a good boy, and we are proud of you. I wish for you to find full satisfaction in your profession. I also wish that your profession of curing doesn’t just become a source of wealth for you but that you yourself become a benefactor to the suffering of humanity.” (Schirm, 2019, p. 269) The Holzer Student Health Center is but one example of Oswald and Ruth Holzer’s service to others.

A Life Well Lived

The students, faculty, and staff at Florida Tech who knew Oswald Holzer will always remember the sparkle in his eye, his contagious laughter, and his gentle, self-effacing irony. On March 8, 1940, in a letter sent from China to his cousin Hana Winternitz in London, Holzer observed: “You know, when one gets out into the world, only then is one able to see what a conceited simpleton he has been. I realize more and more how unworldly, and in a way provincial we are. And so, Adolf provided us with at least this profit, albeit we paid dearly for it.” (Schirm, 2019, p. xxvi) Sound advice from an immigrant who found a home in America and played a critical role in improving countless lives.

Note: Joanie Schirm’s My Dear Boy is a marvelous read. www.joanieschirm.com

Anonymous. (1981, June). Healthy Start. The Pelican, 8(6).

Anonymous. (February 10, 1970). Keuper Meets with Students. The Crimson, 3(11).

Schirm, J. H. (2019). My Dear Boy: A World War II Story of Escape, Exile, and Revelation: Potomac Books.