The Secret History of How a Progressive Woman’s Passion for the Humanities and Nature Led to a Permanent Home for Countdown College

Dateline: 1961

The little girl’s parents found her throwing one of the family’s prize laying hens up in the air. When her bemused mother asked what she was doing, Virginia [nee Pierce] Wood responded she was trying to teach the chicken to fly. It was a simple matter. Birds, the little girl insisted, were supposed to fly. Chickens were birds. “I was sure,” Virginia Wood later explained “that if someone showed them the way and gave them a chance, they could learn.” (Crepeau 1987) Virginia [nee Pierce] Wood lived a remarkable life. She would marry a general, organize a city’s relief in the darkest days of the Great Depression, launch the American Homesteading Foundation (AHF), establish Melbourne Village, and found an institution (the University of Melbourne) dedicated to solving the world’s problems. Later when that effort failed, Wood befriended a young physicist named Jerry Keuper helping him acquire the land that became the core of the Florida Institute of Technology’s (BEC) Melbourne campus. In 1963, Keuper asked Wood to join the college’s Advisory Committee. Three years later, Virginia Wood was named along with Homer Denius, George Shaw, Fred Roberts, and V. Conner Brownlie a founding member of the BEC’s Honorary Alumni Association. In 1970, Wood Hall was dedicated in recognition of Virginia Wood’s service to the university. This was a woman who spent her life, giving wings to the hopes and dreams of others.

Born in 1888, Virginia Pierce grew up on a forty-acre farm outside of Dayton, Ohio. As a child, she remembered her teachers telling her to “think for herself” and strive to make life better for others. Later, as an undergraduate at Smith College, Wood pursued her interest in sociology focusing her studies on the problem of multi-generational poverty. Two weeks after graduating, Virginia Pierce returned to Dayton to marry George Wood, an army general officer twenty years her senior. During World War I General Wood served as adjutant general of the state of Ohio and later in the Rainbow Division of the American Expeditionary Forces. After the war, Virginia Wood became active in the Dayton Bureau of Community Service. Working to provide opportunities for young women at the YWCA Wood encountered a young PhD named Elizabeth Nutting and her housemate Margaret Hutchinson. The three young women became fast friends. They shared a commitment to making a difference in the lives of those around them. Nutting and Hutchison introduced Wood to the work of Ralph Borsodi, a self-educated philosopher and social reformer. In the mid 1930s, Wood, Nutting, Hutchison, and Borsodi secured federal funding for a community relief initiative. These experiences led the three women to formulate the idea of creating the American Homesteading Foundation (AHF). America’s entry into World War II, however, prevented the women from acting until 1946 when the AHF received its official charter from the State of Ohio.M

Melbourne Village Takes Shape

In 1947, Virginia Wood came to Melbourne, Florida looking for a suitable a location for the AHF community. She found a piece of land located just outside the Melbourne city limits on the Kissimmee (US 192) Highway. This was the beginning of Melbourne Village. Inspired by Ralph Borsodi’s critique of what he called the “ugly civilization” that America had become, the AHF’s founding mothers envisioned a community in which individuals would own enough land to be self-sufficient. Education was the key to the project’s success. Wood believed that people needed to learn how to work and live together in productive ways.

From its beginning, Wood recognized that the AHF’s success depended in large measure on two things: establishing good relations with the neighboring communities and finding competent guidance in the community’s day-to-day management. She found both qualities in Norman Lund. Lund had come to Melbourne in 1924 as part of the engineering team laying out US 1. He had liked the sleepy little town on the Indian River and decided to stay. Lund’s success as a businessperson, his position as President of Melbourne’s Chamber of Commerce and his decades of experience in construction made a lasting contribution to Melbourne Village.

Between 1947 and 1952 Wood and Lund guided the Village’s development. Wood, who continued to live in Dayton, made frequent trips to Florida to keep track of the Village’s development. With Lund’s guidance, houses were built, and roads laid out. At times, Lund admitted that the AHF’s founders’ objectives times mystified him. Nevertheless, he did not doubt Wood, Nutting, and Hutchison’s sincerity. The women conceived of Melbourne Village as more than streets and house. Following Ralph Borsodi’s lead, they envisioned Melbourne Village as an on-going educational experiment.

Launching the University of Melbourne

In 1953, Ralph Borsodi arrived in Melbourne after a yearlong round the world trip. While in Asia, Borsodi developed the idea of launching a university that would be dedicated to coming up with practical solutions for humanity’s problems. Borsodi believed that Melbourne Village could serve as the university’s foundation. During the next twelve months, Borsodi won Virginia Wood, Elizabeth Nutting, and Margaret Hutchison’s support for his idea. In 1954, Borsodi and Wood submitted plans for the university at a special town meeting. Borsodi described the university as “an institution of higher learning devoted to the arts and sciences of living and a graduate school limited to thirty students, half from the Orient and half from Europe and the United States.”(Crepeau 1987) Borsodi told the meetings’ participants that he university’s curriculum was be based on his “praxeological philosophy” seeing practical solutions to “the major problems with which living confronts mankind.”

Ralph Borsodi was an individual who provoked strong feelings. To some he was an inspired visionary; others considered him an opinionated martinet. By the meeting’s conclusion, it was clear that a majority of the Villagers opposed the project. Borsodi’s proposal would have floundered at this point if it had not been for Wood’s intervention. Wood knew a local businessman and real estate speculator named V. Conner Brownlie who was planning to develop a subdivision just east of the Melbourne city limits. Wood suggested to Brownlie that a “university” would enhance the subdivision’s value. Brownlie agreed and offered thirty-five acres of land west of Babcock Street as the University of Melbourne’s campus.

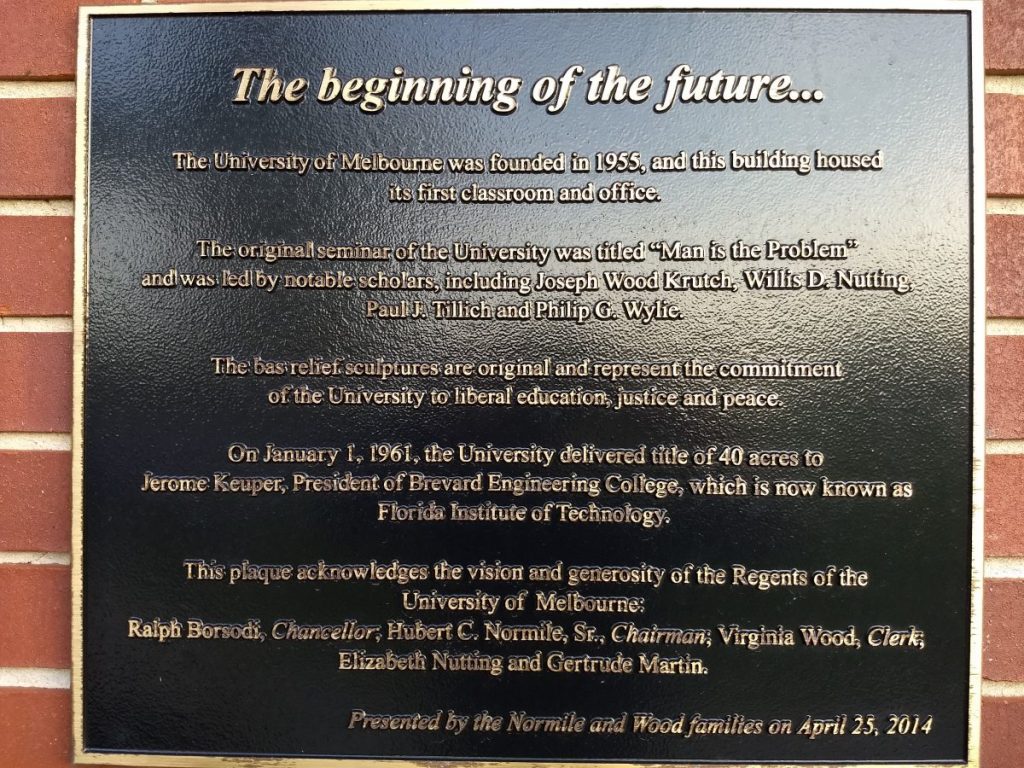

A perusal of the documents outlining Brownlie’s bequest, however, revealed a monumental stumbling block. In keeping with the era’s racist prejudices, Brownlie had placed a deed restriction on the land stipulating that “said property shall be used for the education of white students only, and no persons of the colored race shall be allowed to reside on said property or attend any school constructed on the property.” (Crepeau 1987) This was unacceptable to Wood and her progressive allies. In September, the University of Melbourne’s regents gave Brownlie one week to remove the deed restriction. Brownlie agreed and on October 6, 1955, the corner stone of for the University of Melbourne was laid. In recognition of the university’s multi-racial, educational aspirations, Wood and her colleagues commissioned an Orlando artist to prepare two bas reliefs celebrating the role of education and diversity.

The University of Melbourne held its official opening on 23 September 1956. Alex Boyer, rector of Holy Trinity Episcopal Church, asked for divine guidance in furthering the university’s “praxeological” mission. Elizabeth Nutting’s brother, Willis, agreed to take a year’s leave of absence from Notre Dame to serve as the University’s chancellor. Borsodi and Nutting planned to recruit the school’s faculty from diplomats serving in the United Nations. Students would be drawn from Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Despite Father Boyer’s intercessory prayer and Willis Nutting’s best efforts, only one student signed up for the university’s classes and no foreign emissaries made their way to Melbourne. Over the next two years, the University of Melbourne fielded a handful of sparsely attended seminars.C

Garrett Quick, and Harold Dibble

Countdown College (BEC) Saves the Day

The failure to attract students posed a serious problem. Conner Brownlie had stipulated that the University of Melbourne must demonstrate that it was a viable enterprise. Wood and her fellow regents feared Brownlie would demand that the property’s return. Wood’s friend, Norman Lund, came up with an idea to forestall the university’s default on its contractual obligation. Lund had learned that a young physicist named Jerry Keuper planned to launch a scientific, technical institute called Brevard Engineering College (BEC). Lund, who had agreed to serve on BEC’s board of directors, suggested that the regents allow Keuper to use of the University of Melbourne’s building to register students. In 1958, Wood agreed and a few days later the Melbourne Times announced during the week of July 7, BEC faculty members would be on hand evenings to meet with prospective students. In the mornings, Gertrude Martin, Virginia Wood’s friend who was one of the “founding mothers” of Melbourne Village, volunteered to serve as BEC’s registrar.

Wood’s admiration for Jerry Keuper grew in the next two years. The rocket scientist’s enthusiasm was infectious. Moreover, Wood respected his resolve in standing up to the local school board when it sought to block African-American students from attending Countdown College. In the summer of 1958, Keuper had won agreement from Woodrow Darden, county superintendent of schools, for renting three classrooms at Eau Gallie Junior High School. The relationship between the school system and BEC soured when Darden learned that a pair of African-American “missilemen” were attending classes in the segregated junior high school. Julius Montgomery, one of the African-American students, went to Keuper and volunteered to withdraw in order to forestall Darden’s threat to bar BEC’s use of the classrooms. Keuper credited Julius Montgomery with saving the fledgling college and promised that Montgomery and African-American students would be welcome once the college found a home.

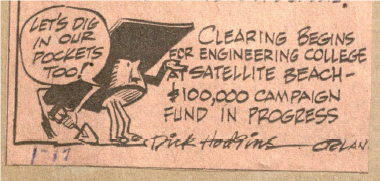

Keuper’s Dilemma: Have College, Need Campus

Keuper’s search for a permanent home for the college would continue for the next two years. In this period, BEC met in an abandoned church just off US 192 and at a World War II vintage building located at the Melbourne Municipal Airport. In December 1959, Jerry Keuper announced that he had received a “sleeper offer” of twenty-acres next to Patrick Air Force Base in Satellite Beach. Percy Hedgecock and W. Lansing Gleason were instrumental in formulating the proposal. “Backed by this kind of widespread interest and community spirit,” an ecstatic Jerry Keuper declared in a newspaper interview, “we can surely build a great institution of higher learning here in Brevard County.” In January 1960 bulldozers began clearing the twenty-acre site in Satellite Beach. Clearing the land proved easy. Finding money for constructing buildings was more difficult. Keuper estimated that $100,000 was needed before construction could begin. The beachside fund-raising campaign, however, failed to mobilize support.

By the fall of 1960, it was clear that there was insufficient community support for the Satellite Beach initiative. Virginia Wood, Hubert Normile, and Homer Denius, came to the college’s rescue. Wood, Normile, and Denius proposed that the BEC make its permanent home in Melbourne. BEC’s long-standing relationship with the University of Melbourne was the key. Wood and Normile, representing the University of Melbourne trustees, offered Keuper a one dollar a year, ninety-nine-year lease on the University of Melbourne’s forty-acre campus. Homer Denius, president of Radiation, Inc. sweetened the proposal by pledging 1,000 shares of company stock to BEC’s building fund. On January 11, 1961, Melbourne’s Daily Times published a banner headline declaring “BEC Gets University Campus.” Three months later in April 1961, ground was broken on the BEC’s first classrooms and the president’s office began.

The Humanities and Botanical Garden Seal the Deal

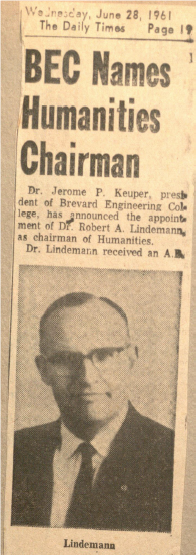

Virginia Wood’s advocacy of BEC grew from her conviction that Keuper and BEC would “strengthen” the University of Melbourne’s courses in the arts and humanities. Within a week of the announcement of BEC and the University of Melbourne’s agreement, Keuper demonstrated his commitment to the humanities. He shared Woods belief that BEC was destined to be more than a narrow technical institute. On January 18, Harold Dibble, BEC’s dean, announced that Rabbi Joseph Liberles, had agreed to teach the college’s first philosophy course. In June 1961, Keuper named Robert Lindemann chairman of BEC’s humanities department. Lindemann, a historian who earned his Ph.D. at Indiana University, was charged with making the humanities a core component in the college’s curriculum. In July, Lindemann announced that Marven Whipple had joined the college’s adjunct faculty and would offer a course in the history of science. Additional courses were proposed in English composition and literature, history, music and art appreciation, economics, logic and psychology.

Years later looking back on this critical moment in Florida Tech’s history, Jerry Keuper credited one factor in winning Wood’s support. “I believe,” Keuper wrote in a memorandum, “the critical factor in our favor was my pledge to maintain the natural hammock that threaded through the property and not to disturb any of the trees unnecessarily. Conservation was of great concern to the University of Melbourne as it was to us.” What would become a Tier 1 engineering and scientific university found its home because of Virginia Wood and Jerry Keuper’s commitment to the humanities and the preservation of what would become the university’s botanical garden. As a kindergarten student, Virginia Wood’s Aunt Sara, had told her to “go ahead and do better” and make a difference in other people’s lives by helping them. As a boy growing up in Fort Thomas, Kentucky, Jerry Keuper dreamed of launching rockets. The little girl and the little boy were cast in the same mold. With energy, encouragement, and, yes, education, rockets get launched, universities founded, and sometimes even chickens can learn to fly.

Ad astra per scientia

Note: The account of the history of Melbourne Village and the University of Melbourne was drawn from Georgiana Greene Kjerulff’s Troubled Paradise and Richard Crepeau’s Melbourne Village: The First Twenty-five Years. See:

Crepeau, R. C. (1987). Melbourne Village the first twenty-five years (1946-1961). Orlando, University Presses of Florida: University of Central Florida Press.

Kjerulff, Georgiana Greene. (1987). Troubled paradise: Melbourne Village, Florida. Melbourne, Fla., USA: Kellersberger Fund of the South Brevard Historical Society.