The Secret History of the Frueauff Energy Building

Dateline: 1977/1983

Prologue: The Three Mouseketeers

The mouse seemed perplexed. It looked as if it had lost its way. Had it forgotten where it wanted to go? Ed Kalajian’s eyes narrowed when the tiny creature moved. This was not Kalajian’s first rodent sighting since the relocation of Florida Tech’s civil engineering department to the Frueauff Building. In the mid-1980s, the dean of the College of Engineering, Tom Bowman, had proposed the move. Bowman had neglected to tell civil engineering faculty that Art Gutman, a psychology professor, had a decade earlier maintained a colony of white mice in one of Frueauff’s bays for experiments in his study of amnesia.[i] For nearly a decade until the civil engineering’s move to the Olin Engineering Building in 1998, the swashbuckling Kalajian and his colleagues Maurice Kurtz and Howard Heck, Florida Tech’s Athos, Porthos, and Aramis[ii] waged an on-again-off-again valiant battle against Gutman’s rogue, forgetful mice.

Kennedy Space Center as Tourist Attraction

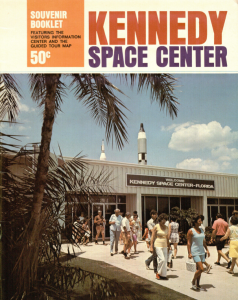

A mouse, albeit a cinematic one, played a central role in the Frueauff Building’s curious odyssey. In the 1960s, what was to become Florida Tech’s Frueauff Building housed the souvenir gift shop and snack bar for NASA’s Visitor Information Center (V.I.C.) at the Kennedy Space Center. The story began in 1963 when Olin Teague, chairperson of the House Subcommittee on Manned Space Flight, advised James Webb, NASA’s chief administrator, that the Agency needed to do something to drum up public support for the space program. To mollify the Texas congressman, Webb and Kurt Debus, K.S.C.’s director, offered to open the space center for weekly automobile tours. On Sunday afternoons, between one and four p.m., visitors would be allowed to drive through the missile complex.

The weekly automobile tours were a huge success. With Teague’s Subcommittee’s support, Webb’s request for a 1.2 million dollars appropriation for a permanent Visitor Information Center at the Kennedy Space Center was authorized. While the permanent facility was under construction, NASA opened a temporary visitor center at the west end of the Indian River Causeway.

The architects for the Visitor Center called for a 42-acre site with two buildings, an exhibit hall with a theater and a souvenir gift shop and snack bar, and a parking lot. The souvenir shop served as the ticket booth for the two-hour bus tours of the space center. On August 1, 1967, the V.I.C. opened to the public. Mr. and Mrs. Gene Sanovich from Willowick, Ohio, were the first visitors. “Amazing,” Gene Sanovich observed, “there’s lots of stuff. It’s a real nice place.” “Everybody,” Mrs. Sanovich agreed, “ought to come down and see where their money is going.”[iii] By 1969, the V.I.C. ranked as Florida’s second most popular tourist attraction. The next year 1.25 million visitors purchased tickets for the T.W.A. guided bus tours at the gift shop ticket booth. Only Tampa’s Busch Gardens drew more tourists. Space Coast business people groused that the only reason Busch Gardens had more visitors was the Anheuser theme park gave tourists a free glass of beer.

The Mouse that Roared

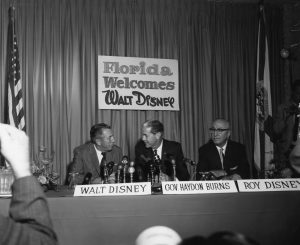

Florida’s money-making potential as a mecca for tourists had not passed unnoticed. In 1965, Walt Disney announced plans for a theme park located in Orlando. Two years later, Disney outlined his plans for Disney World to NASA’s leaders. In the private briefing, “Disney revealed that he was going to spend a lot of money,” a NASA document noted, “on technology for exhibits and shows, a sum that would be impractical for NASA to match. However, he made it clear that NASA had something to showcase to the public he did not — real-world technology in action.”

Mickey Mouse’s imminent arrival in Florida led to radical changes at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Center. In 1971, the congressional Subcommittee on NASA Oversight issued a report assessing the theme park’s impact on the V.I.C. NASA’s consultants believed that a percentage of the tourists who came to Disney World would want to visit K.S.C. They estimated that the number of daily visitors to the V.I.C. would jump from 3000 to 20,000 per day. The V.I.C.’s two buildings were woefully inadequate. Teague’s Oversight Committee recommended a multi-million dollar expansion of the Visitor Center.

Opportunity Comes Knocking

Jerry Keuper knew a good deal when he saw it. When he learned of NASA’s plans to decommission the V.I.C., he proposed that the Agency give one of the buildings to Florida Tech. Negotiations followed, ending in an agreement in which NASA gave Countdown College the building that had served as the souvenir shop and snack bar. The problem was how to get the building from its location at K.S.C. to the university’s Melbourne campus.

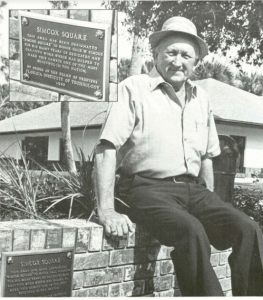

Keuper directed Dale Simcox, Florida Tech’s superintendent of buildings and grounds, to figure out a solution. The project took five years to complete. Later, Simcox modestly described it as a “unique undertaking.” “Miraculous” would be a more accurate description. Simcox drew on the talents of Florida Tech’s groundskeepers Hank Hughes and Jack Thompson. Forty years later, Hughes recalls the daily drives to the space center. Piece by piece, Hughes and Thompson carefully disassembled the V.I.C. souvenir shop building, placed the parts on a flatbed truck, and returned to Melbourne, where they reassembled it on the west side of Babcock Street. It was a colossal undertaking. As a finishing touch, Keuper directed Hughes and Thompson to add a brick façade to the structure’s front.

Surveying the building Keuper observed, “the remarkable results are the product of a dedicated effort by Dale Simcox and his talented maintenance staff. They have combined ingenuity and hard work and are to be commended for being able to do so much with so little.” The Research Building was connected to the main campus by a 260 foot, “picturesque” bridge. Later, the building was renamed in honor of Charles Frueauff, a deceased prominent New York lawyer and financier, whose charitable foundation had donated funds for undergraduate scholarships.

“Hit and Run Alley”

While Jack Thompson and Hank Hughes were putting the finishing touches on the building, district engineers for the Florida Department of Transportation (D.O.T.) and Brevard County were at work on a plan to add two lanes to Babcock Street. A traffic survey revealed that between 7 a.m. and 6 p.m., more than 14,000 cars passed the intersection of Babcock and Southgate Boulevard. The consensus was something had to be done to improve the traffic flow.

The widening proposal, however, provoked controversy. In May 1977, weeks before the Frueauff Building’s dedication, the Melbourne City Council addressed the growing Babcock problem. Residents living in nearby Southgate Manor Estates demanded that safety concerns be addressed before opening two additional traffic lanes. Robert Wing, president of the Southgate Homeowners Association, Inc. dubbed the street “Hit and Run Alley” in his remarks at the Melbourne City Council meeting.

Ben Aaronson, Florida Tech’s student body president, concurred. Aaronson noted that 263 students lived in the Southgate Apartments. On average, the Southgate residents made six trips each day to and from campus. An unsightly drainage ditch on Babcock’s east side made the trips even more perilous. Aaronson feared that it was only a matter of time before a student was killed trying to get to class. A traffic light with a pedestrian signal was needed at the intersection of Babcock and Southgate Blvd. to slow the traffic. Bob Wing agreed, darkly warning that “four-laning of Babcock will add to the difficulties crossing the street, and diplomatic problems could arise if a foreign student attending F.I.T. is hit by a car.”

Despite the students’ and neighbors’ concerns, plans for widening Babcock advanced. By April 1980, Brevard County’s proposal was complete. The plan called for expanding Babcock Street by cutting 45 feet of land from Florida Tech’s campus on the road’s westside. Jerry Keuper objected, arguing that the plan would do irreparable harm to Florida Tech. Access to the Frueauff Building would be blocked, and sensitive scientific experiments jeopardized. Walter Nunn, one of the university’s most distinguished professors, used the Frueauff Building for his research on lasers. In 1979, Nunn secured the donation of an Nd Yag laser from the Control Laser Corporation in Orlando. Nunn planned to use the 20,000-watt laser in his research on treatments of cancer. In a newspaper report, university officials argued that the “encroachment on the lab [Frueauff Building]” and “resulting vibration and noise could be detrimental to sensitive measuring and experiments taking place.” The news reports did not mention Gutman’s mice.

The Mouseketeers and Ma Bell to the Rescue

Ed Kalajian and his colleagues in Florida Tech’s civil engineering department came up with an alternative plan. Why not, they argued, shift the widening project to the east side of Babcock Street where there was an unsightly drainage ditch. Bill Taylor, Brevard County public works director, opposed Florida Tech’s proposal arguing that the “change would require installation of [a] drainage pipe, which would almost double the current 4 million dollar project,” adding at least $3.6 million to the project’s cost.

Southern Bell proved to Florida Tech savior. Company officials estimated that the county’s plan would cost the telephone company 7.5 million dollars in digging up and relocating their underground cables. Bell administrators offered to pay 1.5 million dollars to help in defraying the cost for the road’s expansion. In May, Brevard County commissioners voted to accept Southern Bell’s offer. “It is now, in my opinion, a much better project,” County Commissioner Val Steele declared. “It’s going, Steele added in reference to the Southgate homeowners’ concerns, “to make Babcock safer with a better design and traffic flow. The original plan would have required a guard rail right next to the road, but that won’t be needed with this alignment.”

Work began late in 1980. The project was complete in November 1982. At 8:00 a.m. on November 23, 1982, the road was officially declared open in a blue-ribbon cutting ceremony held in front of Melbourne Central Catholic High School. A jubilant Jerry Keuper hosted a “thank-you breakfast” for county administrators and representatives of the Chamber of Commerce after the ceremony at the Denius Student Union.

Florida Tech Celebrates

In 1983, Florida Tech celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of its founding. Tom Adams, Florida Tech’s Vice President for University Development, oversaw the event’s commemoration. Tom Adams, who served as Florida’s Secretary of State and Lt. Governor, organized a series of activities that culminated in a gala banquet and dance held at the Percy Hedgecock Gymnasium. Adams, whose office had moved to the Frueauff Building, noted in a 5 p.m. press conference the university’s success devising a plan for widening Babcock. The guests of honor included Bob Graham, Florida’s governor, Barbara Newell, chancellor of the state university system, and Congressman Bill Nelson.

Governor Graham had difficulty hiding his irritation as Adams waxed poetic about the paving project. The two men had a history of crossing swords with Adams. In 1961, Adams became one of the chief advocates of the Cross Florida Barge Canal. The idea was to cut a 12-foot deep canal across north Florida. Graham considered the 500-million-dollar project a boondoggle and environmental catastrophe. In 1985, he and Senator Lawton Childs would block the project. Adams’s reference to widening Babcock Street was a provocation that Bob Graham could not let pass. When Adams handed the governor the microphone, Graham declared, “As you leave this evening filled with joy of this special occasion celebrating the “Salute to F.I.T. take time to look around at the beautiful lawns and trees on this campus. See it now,“ he continued, “because when we complete Tom Adams’ assignment of development, everything will be covered with 3 inches of asphalt to ensure that there has not been any oversight to provide adequate transportation to this county.” Adams chuckled. At Florida Tech it was “un pour tous, tous pour un.”

Epilogue: Years after Florida Tech’s civil engineering department had relocated to the Olin Engineering Building, Ed Kalajian received a call that a hazardous mishap had taken place at the Frueauff Building. Kalajian rushed to the scene and discovered Melbourne Fire Department personnel preparing to enter the building. They looked, he recalled like an assembly of “Dark Vaders.” With axes in their hands, they were preparing to enter the concrete material laboratory. The firemen told Kalajian that they had received a report that a 55-gallon drum of sulfuric acid had spilled in the laboratory. Kalajian told the firemen that there was no sulfuric acid in the concrete lab and prevailed upon the firemen to let him enter the building. Kalajian discovered that a lab assistant had left a pot of sulfur on a stove. Fumes from the molten sulfur whiffed across the hallway to Professor Walter Nunn, whose laboratory was next door. Nunn reported the “rotten egg” smell to a colleague. As the story passed from one person to another, it grew. There was one potential benefit. The mice decamped.[iv]

[i] The use of mice in scientific studies has a long history. In the 17th century William Harvey performed experiments using mice in his research on the heart’s role in the circulation of blood. In the 19th century, Gregor Mendel employed mice in his initial studies of inheritance. Mendel, however, stopped using mice because his superior, Bishop Anton Ernst Schaffgotsch, objected that the mice were “smelly creatures that, in addition, copulated.” See: Hedrich, Hans, ed. (2004-08-21). “The house mouse as a laboratory model: a historical perspective”. The Laboratory Mouse. Elsevier Science. ISBN 9780080542539. Art Gutman began his use of mice as part of his graduate work at Syracuse University in the 1970s before coming to Florida Tech. For an example: Palfai, T., Kurtz, P., & Gutman, A. (1974). Effect of metrazol on brain norepinephrine: a possible factor in amnesia produced by the drug. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 2(2), 261-262.

[ii] Athos, Porthos, and Aramis were the protagonists in Alexander Dumas 1844 novel The Three Musketeers.

[iii] An audio file of the V.I.C.’s opening is located on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ndyKICzJhqI&list=ULJUPm3iG55QI&index=198

[iv] Since 2014 NASA has conducted nearly a dozen experiments testing the behavior of mice in its Rodent Hardware System on the International Space Station. The experiments demonstrated that the mice in NASA’s orbiting Rodent Habitat Module did “all the things that they normally would [do]: feeding, grooming their fur, huddling together and interacting with other mice.” See: https://www.nasa.gov/feature/ames/studying-behavior-in-space-shows-mice-adapt-to-microgravity

For a NASA video tour of the V.I.C. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWQsrYPnsHo