Secret History: The Cutting Edge: Presidential Searches at Florida Tech

Dateline: 1958/1986/2001/2015/2022

“A college president,” the late Steven Browning Sample, who served as U.S.C.’s president for nineteen years, once observed, “is like a lawnmower at a cemetery: He has a lot of people under him, but they don’t pay much attention to him.” What follows is a summary of the history of Florida Tech’s presidential searches written from the perspective of a professor under the blade.

The First Search

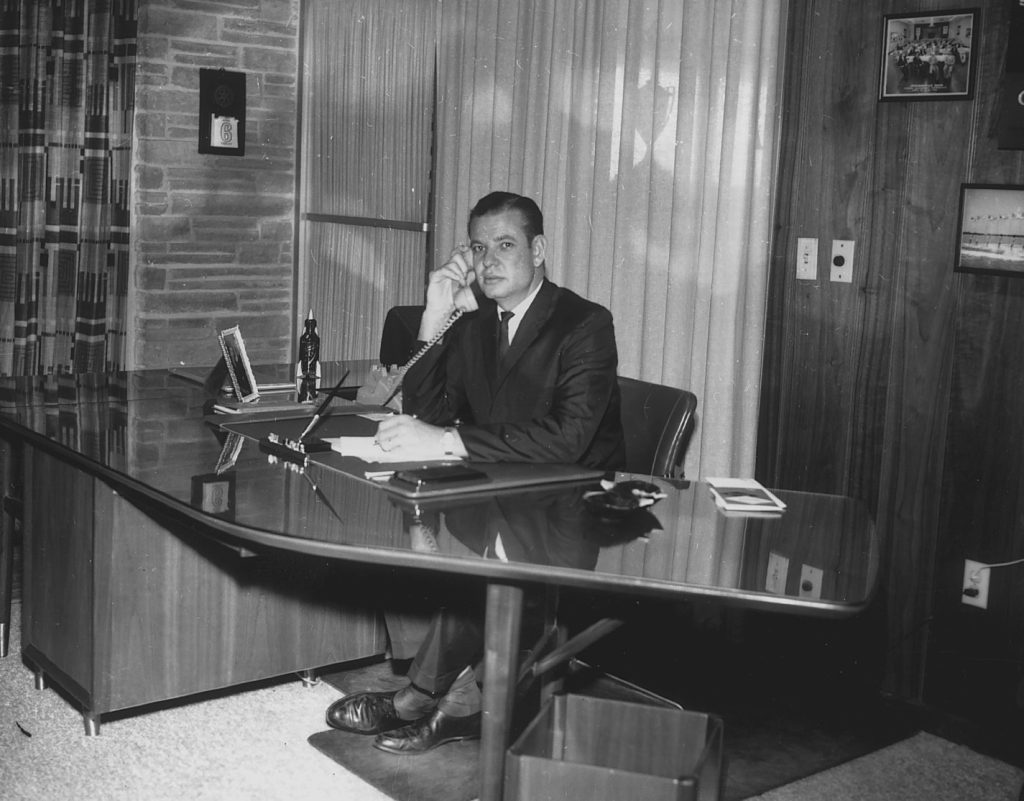

The first search was easy. If you start a college, you get to choose the president. At least that is the way Jerry Keuper saw it. In December 1957, Keuper made a whirlwind visit to Florida, where he interviewed for a position in the Systems Analysis Division of the Radio Corporation of America (R.C.A.). Eight weeks later, Keuper began work at the Missile Test Project. After settling in at the Cape, Jerry Keuper approached his old friend Jim Stoms with an idea. Keuper asked Stoms to join him in launching a college in Melbourne. Madge Stoms overheard the conversation. “Oh, no, you don’t, Jerry Keuper!!!” Madge Stoms declared, “You’re not going to get Jim in any more of your nefarious schemes.” Keuper responded that it was too late. He planned to make her husband the college’s first dean. “How about the president,” Jim Stoms quipped. Keuper responded, “No, that job has already been taken. Too late.”

The Second Search

Seventeen years later, Keuper confided to his old friend that he thought it was time to retire. The closing of the Jensen Beach campus, the disastrous purchase of Hawthorne College in New Hampshire, and a host of other problems had worn him down. On June 30, 1986, Keuper handed responsibility for the university to John Miller, Florida Tech’s executive vice president for academic affairs. Miller agreed to serve as the university’s president until the Trustees named Keuper’s successor. Jim Lyons, the Board’s chairman, headed the search. The search committee prepared a document describing the university and advertised for applicants. One hundred individuals responded to the committee’s call. In mid-August Lyons announced that the names of the three finalists: John Miller; Donald Glower, Dean of Ohio State’s College of Engineering; and Tomlinson Fort, Jr., vice president of California Polytechnic State University. (Mittman, 1986b) Miller, the faculty’s favorite, was considered the inside candidate. On August 29, 1986, the twenty-three members of the Board, however, surprised the Florida Tech community and named Donald Glower Florida Tech’s president.

“Donald Glower,” Bill Potter, the Board’s vice-chairman, stated, “will lead our university to the next plateau of academic excellence and toward our vision of this institution as one of the most highly regarded in the world.” Potter explained to a Florida Today reporter that “the search committee believed that Glower’s strongest point is his record of establishing ties and support between universities and related local industries.” Jim Lyons agreed. “It feels good to have the search over with and to know who is going to lead this university forward.”(White, 1986)

The “good feelings” did not last. One month after his selection, Donald Glower notified the Board that he would not accept Florida Tech’s presidency. A required physical examination revealed an unspecified medical condition forcing Glower’s withdrawal. When asked for the Board’s reaction, a stunned Lyons replied, “we are still in a state of shock.” John Miller agreed to continue as Florida Tech’s president until the Board identified Keuper’s successor. (Mittman, 1986a)

During the next two weeks, the Board of Trustees revamped its strategy. Bill Potter, a prominent local attorney and the Board’s vice-chair, agreed to lead an expanded search committee along with Ray Armstrong, Denton Clark, Percy Hedgecock, Bob Thomas, and Jim Lyons. “Additional members will be appointed,” Potter stated, “to serve in an advisory capacity, with those members coming from the faculty, administration, students, alumni, and the local community.”(“Search committee begins work,” 1986) The goal was to have the new president take charge on July 1, 1987.

The committee’s first decision was to hire Heidrick and Struggles, an Atlanta-based search company, to provide professional guidance. In November and December, the recruiting team began compiling a list of potential candidates. The process entailed background checks and a detailed analysis of each individual’s strengths and weaknesses. In January 1987, the head hunters sent Potter’s committee the “in-depth reports” for a group of potential candidates. True to his word, Jim Lyons announced that the search committee would ask for expert advice from local business leaders in evaluating the candidates. Ted Fuhrer, director of the Avionics Division of Rockwell International, and Albert Verderosa, president of Grumman Melbourne Systems Division, joined the committee as advisors. (“Industry leaders to join search committee,” 1987)

The vetting process and on-sight interviews with the search committee lasted five months. In a nighttime meeting on Monday, June 22, 1987, the trustees voted to offer the university’s presidency to Lynn Edward Weaver, dean of engineering at Auburn University. They waited expectantly as Lyons called the candidate. Weaver accepted the position. When asked why he had taken the job, Weaver explained that “what impressed me about F.I.T. is there is a real opportunity to build a strong technological university because of the dynamics between the academic and business communities and the rapid growth in the high-technological industries.” (Mittman, 1987) An ecstatic Lyons added, “Dr. Weaver has the experience and energy to lead F.I.T. to greatness.”

On Monday, August 10, 1987, Lynn Weaver arrived on campus. He radiated energy and determination. His first order of business was to meet with Countdown College’s faculty and staff. He made clear he intended to make radical changes to the university. “We will develop,” he revealed in an interview with an Orlando Sentinel reporter, “[a] the long-range plan while we’re planning the development campaign. I want to do this because I don’t want to wait. Time is important.” Weaver’s marching orders were clear. The university must wean itself from its reliance on student tuition. An endowment must be built. Funded research was essential. Weaver promised that the university should double, no, triple its research grants and contracts within five years. New buildings and laboratories were desperately needed. Weaver promised to launch a capital campaign seeking donations from industry, alumni, and private individuals in the fall.

The Third Search

Fourteen years later, Lynn Weaver could look back with pride on the university’s accomplishments. In 1997, he had secured a 50-million dollar grant from the Olin Foundation. Larry Milas, the Olin Foundation’s director, described the university as a “diamond in the rough.” Fifty million dollars would go a long way in polishing the stone. In 2001, Weaver announced that he would retire in 2002. Ever modest, he gave credit to the faculty, staff, students, and alumni for his accomplishments. “I believe I made a contribution to the university,” Weaver told a Florida Today reporter. “I’ll be leaving it in a better condition than when I found it.” (Buck, 2001b)

Charles Clemente, the former C.O.O. of America Online/Redgate Communications and university trustee since 1999, led the search for Weaver’s successor. In September 2002, Clemente announced that the search committee would consist of: John T. Hartley, chair of the Board of trustees, Richard Baney, Dale Dettmer, Phillip Farmer, Allen Henry, and Robert Long. Faculty representatives included Gerard Cahill, president of the faculty senate, and James Whittaker, associate professor of computer science. Additional members included Ken Revay, representing the alumni association, Robert Sullivan, VP for research and graduate programs, and Jay McNeely, president of the student government

Once again, the Board engaged an executive search firm to identify a roster of highly qualified candidates. As a first step, the company organized focus groups in which students, faculty, and staff were asked for their input on the qualities Florida Tech’s president should possess. Clemente announced that the search committee had identified nearly seventy-five candidates in December. “We’re very excited about the quality of candidates,” Clemente declared. “Some are currently university presidents, and others are ‘rising stars’ that are ready for the next step.” In January 2002, the search committee planned to conduct off-campus interviews to “see how they fit into our situation,” Clemente added. The expectation was that two or three finalists would be invited to campus to meet with administrators, faculty, students, and community members. “We would like,” Clemente concluded, “to be very thorough.” Clemente’s committee would select one of the candidates and formally recommend their candidate to the Board of Trustees. “We need a person,” Clemente emphasized, “who has a vision and a strategic sense. It takes all aspects, administrative, academic, [and] fundraising.” (Buck, 2001a)

On March 22, 1987, Jim De Santis, Florida Tech’s vice-president for external affairs, announced that the Board of Trustees had identified three highly qualified candidates. All three had visited campus in the previous two weeks. Each was given a campus tour and the opportunity to meet with faculty, staff, students, and alumni. De Santis told a Florida Today reporter that he anticipated the Board of Trustees would name Weaver’s successor shortly. Six days later, on March 28, Jack Hartley, the Board’s Chair, announced that Anthony James Catanese would be Florida Tech’s fourth president. “I see this as one of the great, emerging research institutions in the United States,” Catanese explained when asked why he was leaving a more prominent public institution to lead a smaller, private university. He added that he wants to go from being “captain of a jumbo jet to a rocket ship. I look forward to the speed of the spaceship.” (Buck, 2002)

What made Anthony Catanese the stand-out candidate? “The real difference-maker,” Charles Clemente explained, “was that he demonstrated leadership and understands all that it encompasses…quality of students, excellence in the classroom, research and fundraising; he has shown an innate ability to lead in each of these areas.” Undoubtedly, Florida Tech’s trustees were impressed with Catanese’s success in raising $220 million at Florida Atlantic University. In a phone interview, Catanese revealed his secret as a rain maker. “Some of it is just your personality. People give money to people, not institutions.” One thing was sure: Tony Catanese was a personality. The Board was confident that Catanese could bring his magic to Melbourne. (“Florida Tech names committee members,” 2001)

In June 2015, Anthony Catanese announced that he would retire on June 30, 2016. “Serving as president of this wonderful university,” Catanese said, “has been one of the proudest accomplishments of my career. Florida Tech’s rise to prominence is truly exciting and certainly ongoing. This is a very special place, made so by the people—the faculty, staff, students, and alumni.” Phillip Farmer, chairman of the Board of trustees, credited Catanese with being “the right leader at the right time in the evolution of Florida Tech.” In the news release announcing Catanese’s retirement, Farmer added that the Board of Trustees had named T. Dwayne McCay, the university’s executive vice president, and C.O.O., to succeed Catanese as the university’s sixth president. McCay, who had been one of the three finalists in the 2002 search for Lynn Weaver’s successor, was named Florida Tech’s provost in 2003.

The Ides of March

On Friday evening, March 25, 2022, the Florida Tech community received an email from Travis Proctor, chairman of the Board of Trustees, announcing T. Dwayne McCay’s resignation. Proctor expressed the Board’s “thanks to President McCay and his wife, Mary Helen, for their many years of service.” In the interim, the Trustees asked Marco Carvalho, Executive Vice President and Provost, to assume the duties of acting president in the “Office of the President.” Dr. Svafa Gronfeldt was named the Trustees liaison with the Office of the President.

President McCay’s sudden resignation came as a surprise to many. Under his leadership the university weathered two years of the Covid-19 pandemic. Moreover, he had recently announced the Board’s approval of a five-year strategic plan. Planning for a campus health center was underway. The dedication of the 61,000-square-foot Gordon L. Nelson Health Sciences building, President McCay’s singular achievement, was weeks away. President McCay bid farewell to the Florida Tech community. He admonished the Florida Tech community to learn “the lessons of life’s trial and tribulations to become stronger.” (Walker, 2022)

The Fourth Search Begins

In his statement to the Florida Tech community, Chairman Proctor indicated that there would be a national search for a highly qualified candidate. Details for the search for McCay’s successor have not been finalized. Eight of the thirty-three members of the Board of Trustees are Florida Tech graduates. Moreover, individuals like Bill Potter and Dale Dettmar possess the institutional memory of previous presidential searches. If the past is any guide to the future, the Board will engage an executive leadership firm to identify likely candidates. It is hoped that the faculty, staff, students, and alumni will participate in the process.

Eleven days after President McCay’s resignation, Florida Tech’s Faculty Senate offered the faculty’s assistance to the Board in the search process. The Faculty Senate passed a resolution calling on “the Board of Trustees to conduct a national search of multiple candidates, consistent with the principles of equity and inclusion, for Florida Tech’s President, with the expectation that the selected candidate shall take office on or before the commencement of the 2023-2024 academic year” and respectfully requesting that “the Trustees establish a single search committee to review the credentials, interview candidates, and make recommendations to the Board of preferred candidates, with at least one half of the search committee comprised of faculty, administrative staff, students, and alumni.”

What Lies Ahead

U.S.C.’s Steve Sample likened a college president to a lawnmower at a cemetery. Florida Tech’s presidents have done more than cut grass. Each of the presidents had a vision of what the university could become. Their success hinged on their ability to communicate their vision and secure the faculty, staff, students, alumni and board’s support. This is why an inclusive and transparent search is the surest way to achieve this.

Change is tough for individuals and institutions. If the history of Florida Institute of Technology reveals anything, it is that Florida Tech has made a tradition of creating opportunities in times of uncertainty. “It is the long history of humankind (and animal kind, too),” Charles Darwin reminds us, “that those who learned to collaborate and improvise most effectively have prevailed.” What is true of animals is true for institutions. Working together is the key to success.

Ad Astra Per Scientiam Go Panthers

Citations

Buck, B. (2001a, December 21). Florida Tech narrows candidate list. Florida Today, p. 1.

Buck, B. (2001b, August 15). Florida Tech president to retire in 10 months. Florida Today, p. 1.

Buck, B. (2002, March 28). President, Florida Atlantic University, since 1990; Florida Tech fills top job. Florida Today, p. 1.

Walker, F. (2022, March 28). Florida Tech president resigns: McCay cites ‘especially difficult’ years for family. Florida Today.

Florida Tech names committee members. (2001, September 11). Florida Today, p. 1.

Industry leaders to join search committee. (1987, February 23). Brevard Business News.

Mittman, A. (1986a, October 1). F.I.T.’s pick for president rejects job. Florida Today.

Mittman, A. (1986b, August 29). F.I.T. to name new president. Florida Today.

Mittman, A. (1987, June 24). F.I.T. fills its top job. Florida Today.

Search committee begins work. (1986, November 13). Reporter Weekly

White, G. (1986, August 30). F.I.T. picks Ohio dean for president. Florida Today.