Secret History: The First American Computer Science Undergraduate Degree

Dateline: September 1966

Florida Institute of Technology is a special place. Part of the university’s DNA has always been a can-do attitude coupled with a willingness to venture what others have not dared to.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Florida Tech’s leadership in the creation of the nation’s first undergraduate major in computer science. *

Florida Tech’s First “Electronic Brain”

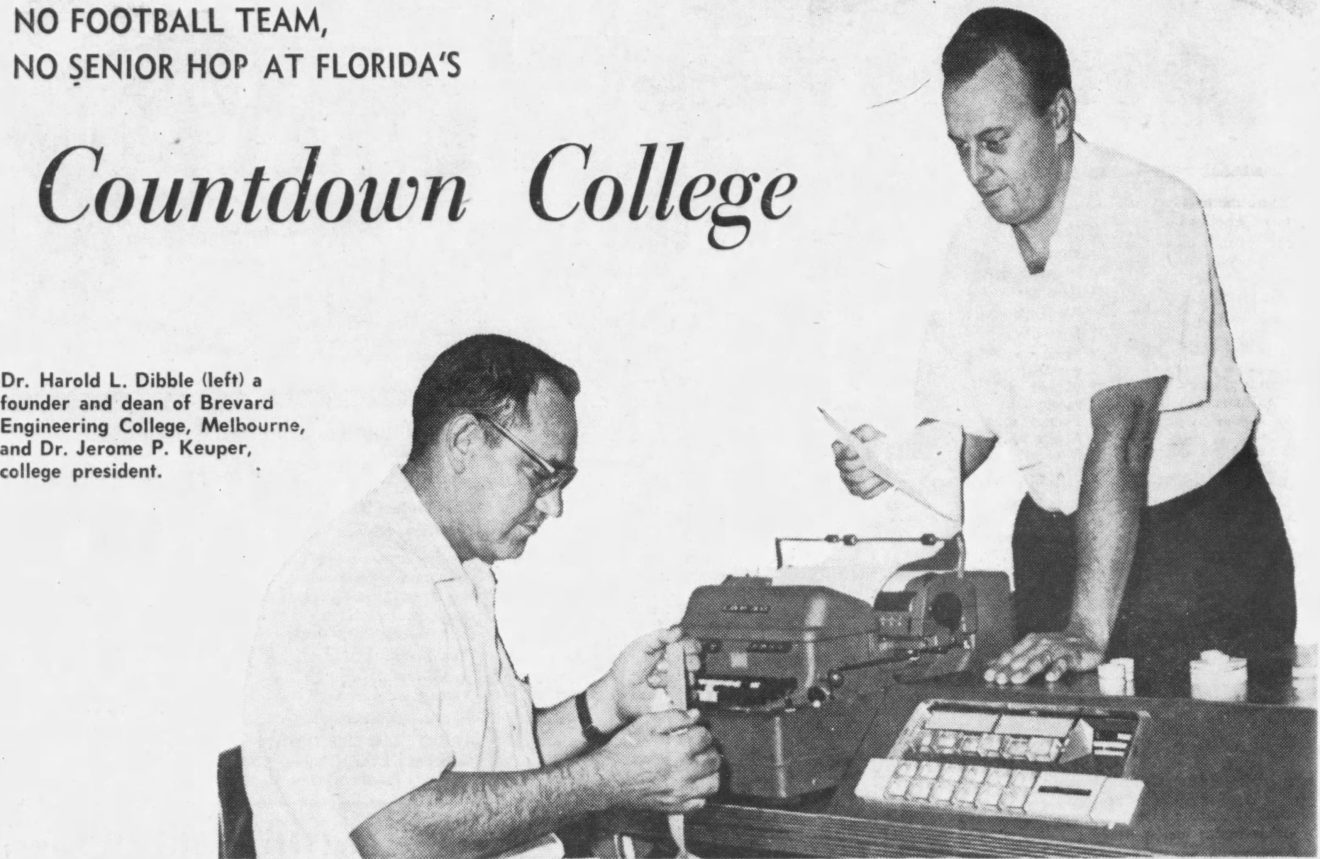

In the weeks following the launch of classes at Brevard Engineering College (BEC) in September 1958, university founder and president Jerome P. Keuper and co-founder Howard Dibble faced a bewildering array of challenges.

Keuper, who had led the mathematics department at Bridgeport Engineering Institute while working for Remington Arms in Connecticut, saw the growing importance of digital computers. He and Dibble wanted to offer a computing course as soon as possible. There was plenty of student interest. The problem was that BEC did not have a computer.

Their solution was to offer a computer course without a computer. On Jan. 5, 1959, the Melbourne Daily Times reported that BEC instructor David C. Howard would teach a graduate course on the “Logical Design of Digital Computers” beginning in February.

Howard, a design engineer at Radiation Inc., planned the course around “the utilization of mathematics as a tool to the logical design of digital systems.”1 Keuper and Dibble approved. There was a lot you could do with a slide rule.

Seven months later in August 1959, Keuper and Dibble finagled “a special arrangement with the Royal-McBee Corporation” to lease a $60,000-plus Librascope General Purpose (LGP-30) electronic digital computer.2

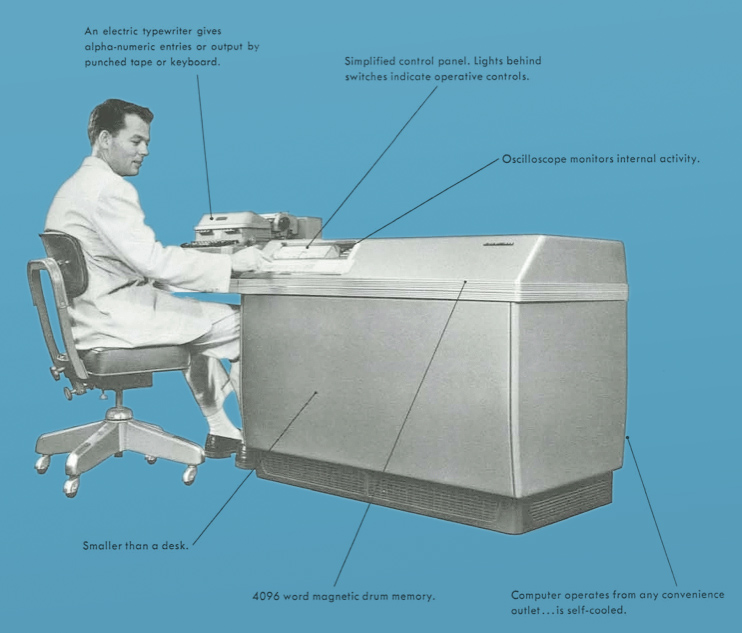

Sporting 113 tubes, the 31 bit and a 4,096-word drum memory, the LGP-30 was one of the earliest off-the-shelf computers.3

The timing was perfect. In July, William McKune had joined Keuper and Dibble at RCA Corp. McKune, with years of experience teaching computer science courses at Georgia Tech, agreed to organize BEC students’ first hands-on experience with an “electronic brain.” McKune, Dibble and Keuper envisioned “visual computing” as a component in what would lead to a bachelor’s degree in either mathematics or electrical engineering.4

McCune had begun work at Cape Canaveral in July 1959. BEC’s enrollment skyrocketed that summer. Hundreds of “missilemen”— scientists and technicians working at the Cape—signed up for classes.

In September, Dibble told members of the Eau Gallie Kiwanis Club that he “anticipated 500 to 600 students” taking courses in BEC’s new home in the old First Methodist Church off Strawbridge Avenue in Downtown Melbourne.4 A year earlier, there had been 115 undergraduate and 60 graduate students.

Recruiting students was not a problem. Finding and keeping qualified instructors was a different matter.

RCA and Radiation Inc. supplied most of the faculty. The press of work at the Missile Test Project and Radiation Inc.’s rapid growth meant that individuals, like Howard and McKune, were often unable to continue teaching on a regular basis.

An “Electronic Brain” needs Tender, Loving Care

By 1961, the ever-parsimonious Keuper acknowledged that maintaining the LGP-30 and developing BEC’s computer courses required full-time attention. Hiring a full-time employee was a serious matter for a college running on a shoestring budget.

The LGP-30, however, would not take care of itself. In April, Keuper announced that he had appointed Marybelle Modell director of the computer center.

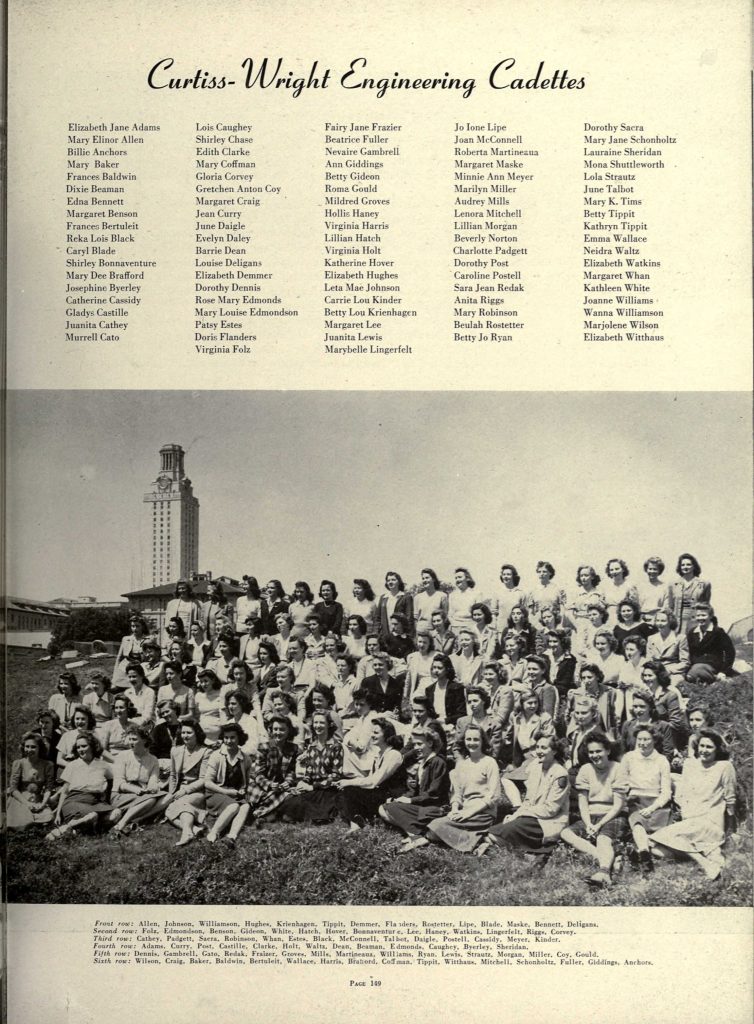

Keuper could not have found a more qualified individual. In 1944, Modell, who was majoring in mathematics at Middle Tennessee State Teachers College, was identified in a national search as one of 918 female college students who were “mathematically advanced” and invited to take part in a government-sponsored initiative to meet the nation’s wartime engineering needs.

The program grew out of Curtiss-Wright Corp.’s inability to find replacements for engineers who were drafted. Overnight, the 20-year-old Jewish girl from Tennessee found herself in Austin, Texas, as one of the Curtiss-Wright Cadettes.

The Cadettes were promised support in completing their engineering education and employment after war’s end. The goal was to cram a 2.5-year engineering curriculum into 10 months of rigorous training.

The program ended in 1945 with the war’s conclusion. Many of the Cadettes discovered that Curtiss-Wright had forgotten its promises. Modell, however, soldiered on, completing her degree in aeronautical engineering at the University of Texas.5

The post-war era was a difficult time for a female engineer. Jobs for the Cadettes and women employed in the war effort vanished with the return of the GIs.

After a short stint at Curtiss-Wright, Modell worked for Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corp. as a systems design officer and on the SPEEDAC computer at the Sperry Gyroscope Company.

In 1955, Sperry acquired Remington Rand, becoming Sperry Rand, the developer of a family of UNIVAC computers.

For a time, Modell served as one of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics’ (NACA) “East Computers” at the Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. “East Computers” was the code expression for white mathematicians in the Jim Crow 1940s and 1950s.

During this era, Modell’s African American female colleagues were restricted to Langley’s west facility and were known as the “West Computers.”6

By the decade’s end, Modell had put NACA behind her and joined RCA as an applied mathematician and programmer working with Keuper. Keuper knew talent when he saw it. He recruited her to serve as the first director of BEC’s computer center in April 1961.

Modell was destined for disappointment if she’d hoped to escape the constraints of racism and sexism as a pioneer in the burgeoning field of computer science.

Two weeks after joining BEC, the Orlando Sentinel published a report that “Computer Men Form New Chapter” of the Association for Computing Machinery (AMC). The predominantly male association (no women were listed in the newspaper report) was led by president David Clutterham and vice president Charles Pearson, who worked for the Martin Marietta Electronics and Missile Group in Orlando, Florida.

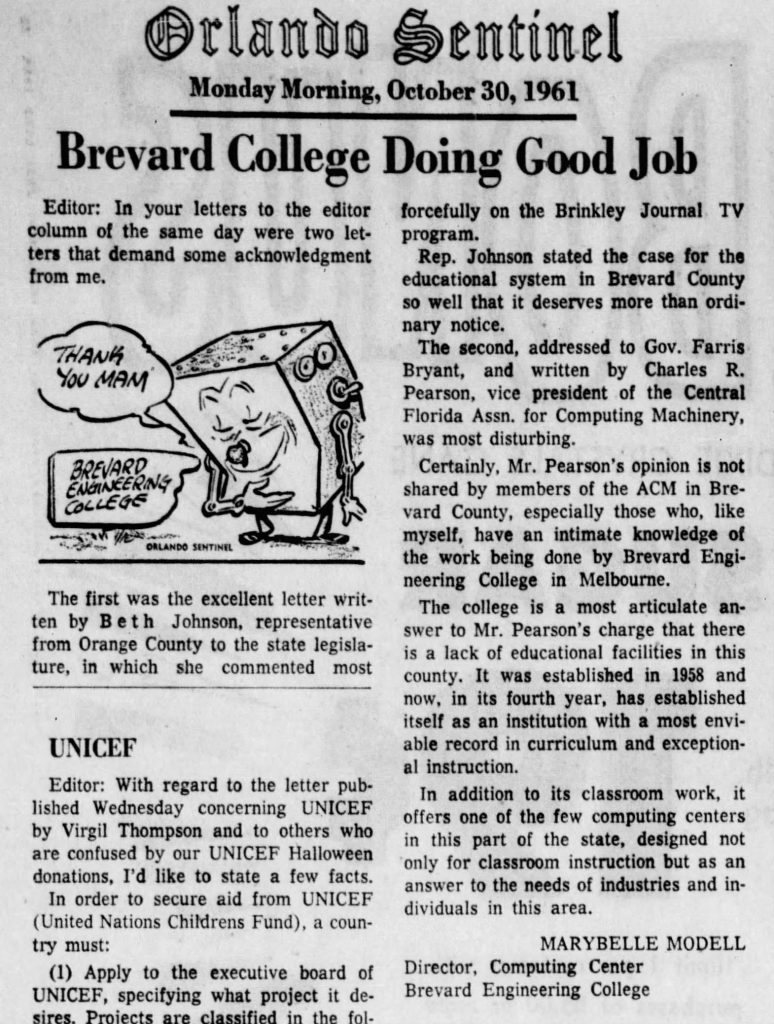

Modell was a fierce champion for BEC. When the Orlando Sentinel published a letter from Pearson to Gov. C. Farris Bryant bemoaning the absence of an engineering school in East Central Florida, Modell penned a sharp retort.

“The lack of such an educational facility has slowed the flow of [scientific] talent, and hence also industry requiring this kind of talent to this area,” Pearson opined.7

Modell fired back.

“Mr. Pearson’s opinion is not shared by members of the ACM in Brevard County, especially those who, like myself, have an intimate knowledge of the work being done by Brevard Engineering in Melbourne. The college is a most articulate answer to Mr. Pearson’s charge that there is a lack of educational facilities in this county. … it offers one of the few computing centers in this part of the state.”8

In Search of Greener Pastures

Modell established a fast-paced routine at BEC’s computer center. Her days were divided between meeting BEC’s digital processing needs while simultaneously looking for external industry clients for the LGP-30.

“A cry for help went up, and a local lady aeronautical engineer and her humming-clicking-machine found the solution in a few hours. … Mrs. Modell, the director of the Brevard Engineering College’s Computing Service, had ‘taught’ the computer to solve problems such as the one that stumped the engineers,” Frank Karel reported in the Miami Herald.9

The money earned from business clients was a valuable infusion to the cash-strapped college.

In 1962, Modell left BEC to open Modell Computing Service on Strawbridge Avenue in Melbourne, Florida.

Her success in winning clients for BEC convinced her that the future was bright for data processing in what the Orlando Sentinel described as a “computer-conscious section” of Florida.

Sadly, the business did not prosper. In 1963, Modell left Florida, remarried and relocated to Ohio.

Edward A. Robin to the Rescue

Demand for computer science courses grew in the next 18 months.

“Computing, one of the most vital sciences of the Space Age, is receiving new emphasis at Brevard Engineering College,” BEC dean Thomas Putnam told a Miami Herald reporter.10

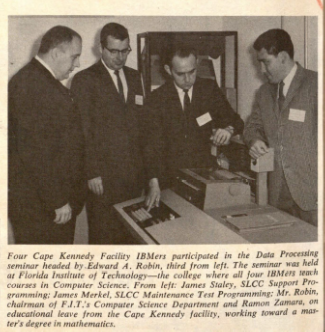

The engine behind these developments was a 20-something Huntsville IBM engineer named Edward Robin, who had come to the Cape to serve as the company’s launch site programming manager.

Keuper recognized a kindred spirit when he saw one.

Robin was energetic and disciplined. In December 1965, BEC announced plans to offer the first undergraduate degree program in computer science in the U.S. Three years earlier, Purdue University had inaugurated the first American graduate degree in computer science, and Keuper and Robin believed the time was right.

“We will take a cross-section of the disciplines needed,” Robin explained in IBM News, “and integrate them into our program. … The program … will be broad. Graduates will be qualified for a number of positions in the computing field, including system engineers, programmers, and logic designers.” BEC’s computer science curriculum “was designed to prepare students to be the leaders of tomorrow in the computing field.”11

IBM’s support for BEC began in 1965, when the company sponsored an “Introduction to Computer Science” course.

One of Robin’s IBM colleagues at the Cape, James Merkel, served as the class’s instructor. With Keuper’s encouragement, Robin took responsibility for the new major’s design.

By the end of February 1966, Robin had convinced three of his IBM colleagues to join the BEC computer science team.

In September 1966, one month after BEC officially changed its name to Florida Institute of Technology, the college launched the nation’s first undergraduate computer science program.

The program was part of a sweeping set of initiatives that reshaped the university. The engine of change was a 45-year-old physicist named John Miller.

Miller and Keuper’s friendship dated back to the late 1940s from their graduate work at the University of Virginia. Jesse Beams, the “father of the centrifuge,” served as the chair of both men’s doctoral committees.

In an interview in 1997, Keuper recalled phoning Miller to tell him that he needed a strong academic person. He was desperate.

“Miller was a damned good physicist,” Keuper observed. “He had it made.” Miller held an endowed chair in physics at Clemson University. “John risked everything for the fledgling college. When John arrived, [I] turned everything over to him. I never went to a faculty meeting again.”

Miller, who would serve as the college’s president after Keuper’s retirement, was the architect of Florida Tech’s academic programs.

His objective was academic excellence both in the classroom and in the research laboratories. His genius was his ability to define goals and identify the means of achieving them.

“Miller was excellent with people,” Harry Weber recalled in an interview decades later. One of his first goals was developing a Ph.D. program in electrical engineering. The burgeoning graduate program was important, but Miller knew that the university’s foundation lay in its undergraduates. For this reason, he supported Robin’s efforts.

The undergrad computer science program blossomed. In January 1967, Keuper announced that Florida Tech would open a new computer center.

With Robin’s assistance, Keuper and Miller secured a favorable lease on an IBM 1130 computer.

It is “the only computing service available in this part of Florida,” Keuper explained.

The IBM 1130 dramatically expanded the college’s ability to meet instructional needs while simultaneously supporting faculty research.12

Five years after Modell’s departure, Robert Brown was hired to serve as the computer center’s director. By May 1967, Florida Tech offered 14 computer science courses. Demand was so great for the IBM 1130 that eight of the classes met on Saturdays.

Opportunity Comes Knocking

Robin was a rising star at IBM. In September 1967, he was offered a promotion that entailed his leaving Melbourne.

Upon his departure, Robin donated a collection of computer science books to the college’s library. He was confident the program would prosper.

Clutterham agreed to step in as the computer science program’s part-time head. A year later, he left the Martin Co., accepting a full-time position as chair of the newly created Department of Mathematical Sciences, which merged the computer science and mathematics faculties. Clutterham remained head of the department until his retirement in 1989.

The Sound of Breaking Glass

Robin deserves credit for creating new opportunities for students at Florida Tech.

The launch of the computer science undergraduate major came at a moment in which the university was undergoing tremendous growth.

In September 1967, about 800 students began classes at Florida Tech. In 2021, about 3,500 full-time undergraduates enrolled, of which 1,068 are women. Robin would be proud that 243 of these students are majoring in computer science.

Indeed, Florida Tech is a special place. From its founding in 1958, Keuper envisioned an institution that would meet the educational needs of men and women seeking to better themselves and their world through the study of science, technology and the humanities.

He did not do it alone. Individuals like Robin, Miller, Weber and Clutterham made a difference in countless lives by their dedication.

And, yes, Florida Tech owes a special debt to a Curtiss-Wright Cadette named Marybelle Modell. Like the university she served, Modell was a can-do trailblazer who refused to be defined by the prejudices of her times.

Today, 60 years after her time minding the university’s first computer center, 32 women are majoring in computer science.

Ad Astra Per Scientiam.

Citations

*In correspondence, Edward Robin described Florida Tech’s undergraduate program as “the first” computer science major. Later, Jerry Keuper described it as one of the first. It is probably safest to say the computer science major was one of the earliest and one of the best.

**According to Florida Tech records, the first graduates of the university’s computer science bachelor’s degree program were William Lynn McKinney ’69, Joseph Richburg ’69 and Richard Lewis Ward ’69.

1Graduates’ Study Due in Melbourne. (1959, January 6). Orlando Sentinal Brevard Edition.

2Electronic “Brain” Class Scheduled. (1959, August 20). Miami Herald.

3Frankel, S. P. (1957). The Logical Design of a Simple General Purpose Computer. IRE Transactions on Electronic Computers, EC-6(1), 5-14. doi:10.1109/TEC.1957.5221555

4Pyle, H. (1959, August 7). Engineering Institute Growing. Orlando Sentinal.

5Cochrane, D. (2013). Meet the Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical Engineering Cadettes. Retrieved from https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/meet-curtiss-wright-aeronautical-engineering-cadettes

6Parks, C. (2021). NASA’s West Area Computers. Resource Library Article. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/nasas-west-area-computers/

7Letter to the Editor ‘Engineering School’. (1961, October 16). Orlando Sentinel.

8Modell, M. (1961, October 30). Letter to the Editor “Brevard College Doing a Good Job”. Orlando Sentinel.

9Karel, F. (1961, August 28). Got a Problem? Maybe Electronic Brain Can Help. Miami Herald.

10Degree Planned in ‘Computing’. (1965, December 24). Miami Herald, p. 28.

11IBMer Named Chairman of College’s New Department. (1966). IBM News, 3(Number 4).

12FIT To Operate Computer Center. (1967, January 11). Orlando Evening Star.