The Secret History of the World Center for Liturgical Studies

Dateline: 1972-1976

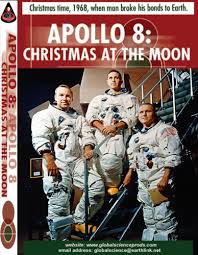

On December 24, 1968, eight months before Neil Armstrong’s “one small step for man,” the crew of Apollo 8, while orbiting the moon, transmitted a Christmas Eve greeting. At the moment of a lunar Earthrise, William Anders, James Lovell, and Frank Borman took turns reading verses 1-10, from Chapter 1, of the King James version of the Book of Genesis. “We close,” they ended their transmission to Houston CAPCOM (Capsule Communicator), “with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas — and God bless all of you on the good Earth.” The next morning, Frank Borman, the mission’s commander, ordered James Lovell to fire the space craft’s engines and begin the journey home. “Please be informed,” Borman remarked whimsically in his confirmation of the successful ignition, “there is a Santa Claus.” At 10:50 AM EST on December 27, 1969, Apollo 8 splashed down in the northern Pacific. (Howell, 2018, p. 14)

NASA and the First Amendment

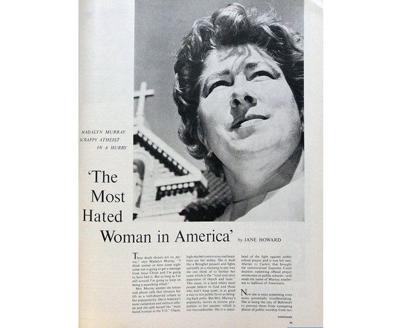

Anders, Lovell, and Borman’s reading from the Hebrew Scriptures provoked immediate controversy. Madalyn Murray O’Hair, sometimes described as the “most hated woman in America” (Le Beau, 2003) and the founder of the American Atheists, filed a lawsuit against Thomas Paine, NASA’s Administrator, asserting that “various religious statements were made on television by the astronauts” and that “the timing of the Apollo 8 flight during the Christmas Season was chosen for religious purposes.” O’Hair maintained that these acts showed a blatant disregard of the First Amendment’s separation of church and state. O’Hair’s brief contained no reference to Borman’s purported sighting of Santa Claus. In December 1969, a three-judge panel at the U.S. District Court for Western Texas ruled against O’Hair. Two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case. (“O’HAIR v. Paine, 312 F. Supp. 434 (W.D. Tex. 1969,” 1969)

Despite the lawsuit’s dismissal, O’Hair’s action set in motion a series of events that eventually led Jerry Keuper and John Miller to flirt with the idea of making Florida Institute of Technology into a center for theological research by providing a home for the World Center for Liturgical Studies. Perhaps even more remarkable, it was General John Medaris, who between 1955 and 1958 had led the Army Missile Agency, the White Sands Missile range, the Jet Propulsion Laboratories, and the Missile Firing Range at Cape Canaveral, who served as the catalyst for Countdown College’s heavenly, curricular ambitions.

An American Original

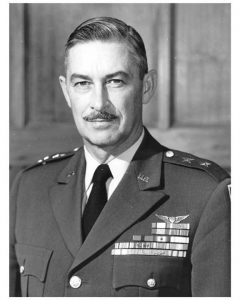

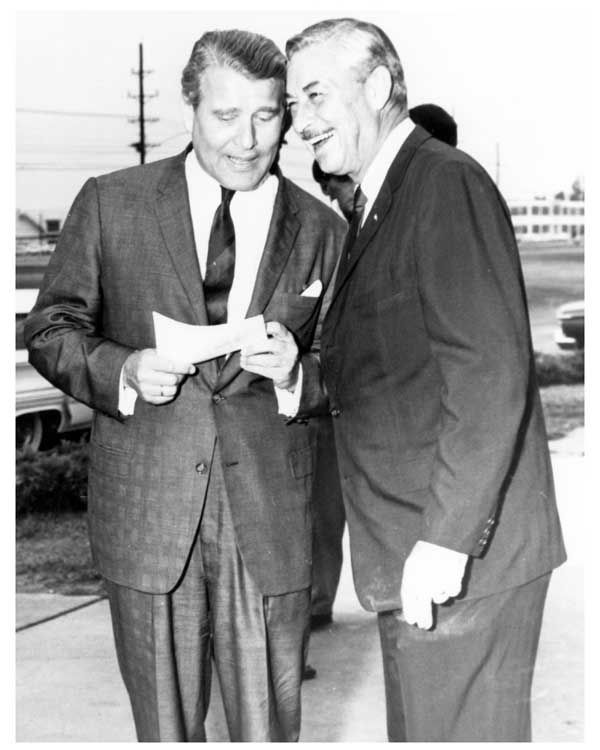

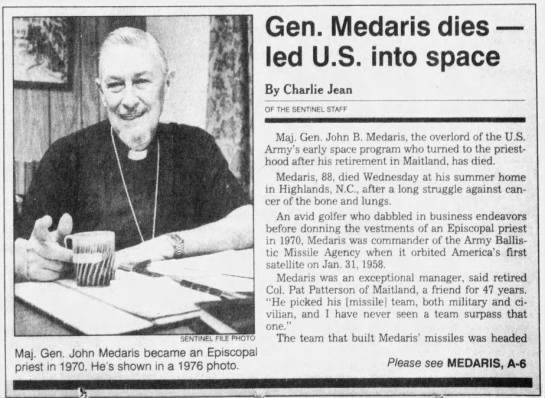

John Bruce Medaris was a highly decorated Army officer when he was named head of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency in Huntsville, Alabama, and the missile test project at Cape Canaveral in 1955. Medaris took charge of the German rocket team which was led by Werner von Braun and Kurt H. Debus at a critical moment. A tall, handsome man who sported a mustache and carried a swagger stick, Medaris was known for his unflinching honesty, no-nonsense demeanor. On one occasion in World War II, General George Patton asked Medaris to inflate the numbers of captured German soldiers. Medaris refused, observing “something is either true or it’s not. And if it’s not, I won’t bend it. Patton, who was known as “Old Blood and Guts,” considered Medaris “a pain in the neck.” Fortunately, Medaris had friends higher up the chain of command. General Omar Bradley, the Army’s chief of staff, shielded Medaris from Patton’s fury. Bradley would later award Medaris his first general’s star. (Harris, 1989)

“A Pain in the …” Puts the U.S. in the “Space Business”

George Patton was not alone in judging General Medaris “a pain in the neck.” When he assumed command of the Missile Test Project, Medaris made it clear to his subordinates in Huntsville and at the Cape that he did not suffer fools gladly. Later, Medaris would describe his relationship with his civilian bosses in Washington as “poison.” (Harris, 1989) As early as 1955, he proposed launching a satellite and bristled when he was ordered to hold back. The Russians successful launch of a 184-pound satellite called Sputnik on October 4, 1957, sent shock waves across the nation. Medaris saw it as an opportunity and swung into motion. Ninety days later at 10:48 PM EST, on January 31, 1958, Medaris gave the launch command for the Jupiter-C rocket which carried the United States’ 31-pound satellite, Explorer 1, into orbit. In the next six months, Medaris fell into disfavor in Washington because of his campaign for the Army’s remaining in charge of America’s space program. His opposition to NASA’s creation led to his transfer to a desk job at the Pentagon and, as a consolation, a third star. In 1960, Medaris retired as lieutenant general and took up residence in Maitland, Florida. (Harris, 1989)

A General and a Rocket Scientist’s Friendship

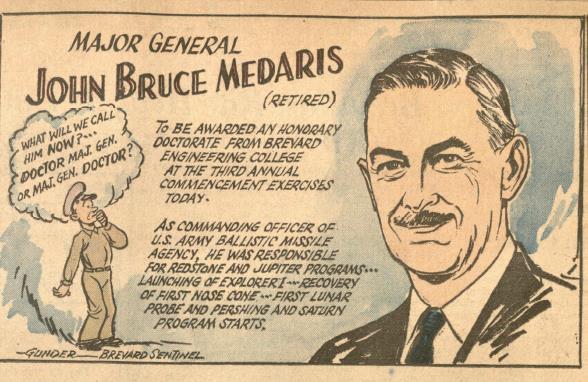

John Bruce Medaris was one of Countdown College’s early advocates. He liked Jerry Keuper’s pluck and energy. Keuper took charge of the Systems Analysis Division of RCA at the Cape in February 1958. Medaris, a strong advocate of education, particularly approved of Keuper’s idea of launching Brevard Engineering College (BEC). In 1963, a smiling Jerry Keuper awarded General Medaris an honorary doctorate in space sciences at Brevard Engineering College’s June commencement. “While the rest of Florida talks about a space technology school,” General Medaris declared in his address to the 21 graduates, “Brevard Engineering College actually does something about it. You’ve come a long way,” Medaris continued, “but your job has just begun. In the field of space technology, you must maintain your education or be lost. Don’t stop now, he cautioned, “or you will be lost. Hesitate once, and this parade will leave you behind.” (Anonymous, 1963)

Five years later in 1968, Jerry Keuper invited General Medaris to be the guest of honor at the dinner commemorating the tenth anniversary of Florida Institute of Technology’s foundation. Medaris was effusive in his praise. “What has happened at F.I.T.,” Medaris told those gathered at the celebration, “is very little short of a miracle.” (Patterson, 2000, p. 60)

A General’s Belief in Miracles

The general’s use of the word “miracle” was more than a rhetorical flourish. In 1964, a stunned Werner von Braun recalled Medaris marching up to his desk and asking the German rocket scientist if he would serve as a pallbearer at Medaris’ funeral. von Braun, who had followed Medaris’ lead and joined the Episcopal Church in Huntsville, had witnessed the general’s initial battle with cancer in 1956. Medaris told von Braun that cancer had returned. His doctors gave him eighteen months to live. (Hinson, 1975) “I was supposed to be dead by Christmas of 1965,” Medaris recalled. “But the Lord had other ideas.” (Gallagher, 1972, p. 9) Medaris would live another twenty-five years waging an on-again, off-again battle against cancer until succumbing to lung cancer in 1990. He was eighty-eight at the time of his passing.

Convinced that God’s intercession had miraculously saved his life, Medaris began “studying for the priesthood, directed by a power much greater than ever wielded during his military career.” (Gallagher, 1972, p. 9) He resolved to dedicate himself in the time that lay before him to serving the Lord. This commitment would culminate in Medaris’ ordination as an Episcopal priest in 1970. During the next decade, “Father Bruce” won the support of Congress and President Richard Nixon for the creation of a Chapel of the Astronauts at the Kennedy Space Center and succeeded in persuading Jerry Keuper and John Miller to make Florida Tech the home for the World Center for Liturgical Studies.

Medaris made no secret of his religious convictions. “I think,” he recalled in an article entitled “A General Looks at God,” “it was in England in 1942 or 1943 [when] I became convinced of the power of the Lord.” To subordinates, he regularly described God as the “owner of the whole show.” When critics objected that a general in charge of the Army’s Ballistic Missile Agency had no business offering theological opinions, Medaris snapped “if God did not want us to explore his kingdom he would have stopped us on the launch pad.” (Anonymous, 1979, p. 53) Looking back at his career as the Cape’s chief “Missileman” Medaris observed, “No one could have had the continuing success in the space area that I did without God’s help.” (Noble, 1997)

The World Center for Liturgical Studies

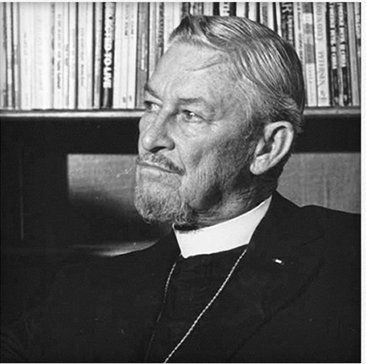

Medaris’ ongoing battle with cancer made him mindful that he had limited time to act on his religious beliefs. In Maitland, Medaris and his wife, Virginia, became active parishioners in the Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd “Soon I found myself,” he recalled “irresistibly forced into (other) situations.” (Folkart, 1990) In 1962, Medaris learned of an “other situation” involving an Episcopal priest named Don Copeland who had proposed the creation of a World Center for Liturgical Studies (WCLS). The previous year Copeland had resigned as rector of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Coconut Grove in order to create an “an institution where liturgical scholars of all Christian traditions can meet to share, study and explore aspects of their common worship.” Copeland’s idea was to create a center for “the promotion of scientific liturgical study” which would form the “foundation for Christian understanding and cooperation.” To Copeland, the discord between different Christian Communions (Roman Catholic, Anglican, Orthodox, and Protestant) was not in “differing conceptions ….of the historic Creeds” but rather lay in the “different patterns of worship.” Copeland’s hope was that WCLS would provide a forum in which these differences could be reconciled. (Copeland, 1963, p. 7)

Medaris, who would become one of the WCLS’s trustees, found the idea particularly attractive. Like Copeland, he believed that many of the disagreements between Christians could be clarified through an examination of different liturgical traditions. The word “liturgy” refers to the arrangement or order of the rites associated with worship. Medaris shared Copeland’s belief that the WCLS would “fill a vital and urgent need at this critical juncture in Christian and world history.” Copeland set ambitious goals for the WCLS. His plans called for raising $8,000,000 for building a conference center, a library, a chapel, and a residential living facility for visiting scholars. The WCLS would be located on a thirty-acre campus in Boca Raton, Florida. (Copeland, 1963, pp. 7,8)

A Chapel of the Astronauts

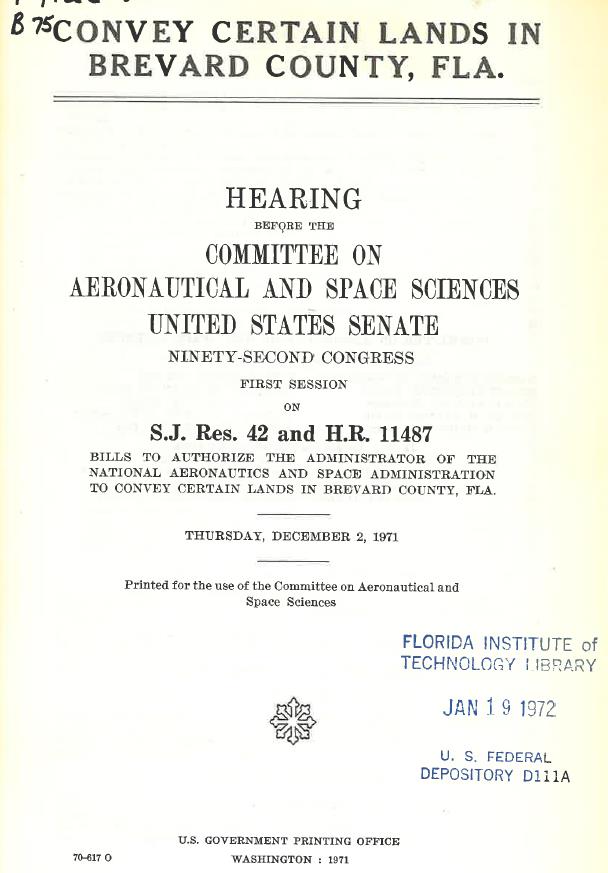

During the next ten years, Copeland and the trustees for the WCLS struggled to raise the needed funds. In 1965, the WCLS relocated to Boynton Beach. By the late 1960s, it was clear that the hope for $8,000,000 capital campaign was not going to succeed. Medaris, however, had lost none of his ecumenical zeal. In fact, while struggling to save the WCLS, the general had become caught up in the controversy that followed the Apollo 8 astronauts’ Christmas benediction. On Valentine’s Day in 1969, Medaris organized a meeting to form a non-profit organization, Chapel Inc., that proposed the creation of a Chapel of the Astronauts at the Kennedy Space Center. In testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Medaris explained the idea’s “Genesis.” “The whole matter really came into focus,” the general testified when he heard, “on Christmas Eve 1968, the voice of a devout mortal man, speaking from further out in the great spaces of the universe than man had ever before ventured, was beamed into the homes of the great majority of America people, reading in the warm measured tones of faith the first portion of The Book of Genesis. (Hearing Before the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, 1971, p. 37)

Senate Hearing on S.J. 42 and H.R. 11487 (December 2, 1971)

By November 1969, Medaris had secured the support of Kurt H. Debus, the Director of the Kennedy Space Center. A month later, Tom Paine, NASA’s Administrator, approved the proposed 5.5-acre site for the chapel. Madalyn O’Hair’s lawsuit, however, complicated the Chapel proposal. Spencer Beresford, NASA’s General Council, “informally consulted with the Department of Justice” (DOJ) seeking an opinion on transfer of property to Chapel, Inc. The DOJ attorneys “declined to advise on the constitutional question, but did indicate that the easement was not appropriate.” (Hearing Before the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, 1971, p. 14) The DOJ’s unofficial opinion was a setback. Medaris, who served as the Chapel Inc.’s president, had a solution. If NASA did not have the authority to convey property to Chapel, Inc., then Medaris proposed that the proponents of the Chapel of the Astronauts should seek legislation that would allow the federal government to sell the property to Chapel Inc. Florida’s Senators Laughton Childe and Edward Gurney rallied support for the measure. Two years elapsed before the joint resolution of S.J. Res. 42 and H.R. 11487 was passed. On February 16, 1972, President Richard Nixon signed into law the bill authorizing the transfer of 5.5 acres of land adjacent to the KSC Visitor’s Center for use as a Chapel of the Astronauts. (Anonymous, 1972b)

The World Center for Liturgical Studies Finds a Home at Florida Tech

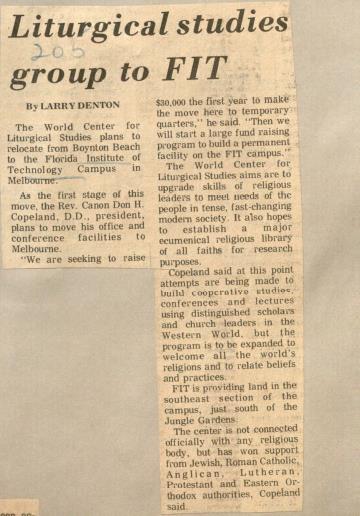

General Medaris, who now described himself as “Father Bruce,” struggled in the next four years to raise funds for both the Chapel of the Astronauts and the WCLS. In 1972, Medaris approached his friends Jerry Keuper and John Miller and asked for help. There was little the two physicists could do to help with the Chapel. F.I.T.’s purchase of St. Joseph’s College (Jensen Beach) in 1972 left the perennially cash strapped Keuper with no discretionary funds. Keuper, however, offered Medaris the use of a house the college-owned at 2801 Vassar Street behind Brownlie Hall. In May, John Miller announced that WCLS would take up residence at Florida Tech. (Anonymous, 1972a, p. 98) “We are very pleased,” John Miller declared, “that the World Center has chosen F.I.T. as the location of its new home. The Center will add to the growing academic stature of F.I.T. and the Center’s activities will be an important asset to laymen and clergy in the Melbourne area.” (Anonymous, 1972a, p. 98) Overnight, the three-bedroom house became the home for the WCLS ecumenical outreach.

The documentation describing Florida Tech’s stewardship of the WCLS is scanty. The Keuper Scrapbooks for June 1973 include a newspaper clipping crediting F.I.T. with providing a home for the WCLS. “The Center,” the anonymous journalist wrote, “is a great story. It has no official connection with any religious body. It is a place where there is interchange directed toward continuing pastoral education, for the cooperation of peoples to preserve universal values and for witness to the importance of religion in a technological age.” (Anonymous, 1973 p. 26) On July 28, 1973, the Keuper Scrapbooks noted that Rev. Medaris “would assume the top directorship post at the center which is located on the campus of Florida Institute of Technology.” (Anonymous, 1973 p. 64) Six months later on March 8, 1974, F.I.T. co-hosted with Florida Council of Churches the WCLS’s first seminar. (Anonymous, 1973/4, p. 88)

The University Counseling Center

Neither the Chapel of the Astronauts or the WCLS were destined to endure. “Father Bruce” and his confederates were unable to raise the needed funds for either the Chapel or the WCLS. In the fall of 1974, Father Bruce told Jerry Keuper that he believed that the WCLS was unsustainable. “It is regrettable,” Jerry Keuper responded on December 1974, “that the World Center for Liturgical Studies fell through. It appears that the newly formed University Counseling Center (UCC) will be rendering, through the ministerial association, a worthwhile service.” (Keuper, 1974) Two months earlier Keuper had announced the university would launch a counseling center. Father George H. Moreau, who held a Ph.D. in psychology and served as a priest in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orlando, was named the counseling center’s director. Eight years later, Father Doug Bailey would assume Father Moreau’s post at what became the Florida Tech’s Campus Ministries and All Faith Center. By then the WCLS had ceased to exist. In 1976, the WCLS’s corporate license was revoked. John Miller, Florida Tech’s executive vice president for academic affairs and John Medaris are listed on the document.

An Enduring Friendship

John Bruce Medaris continued to be one of Florida Tech’s advocates. He believed in the university’s space-age mission. Jerry Keuper, John Miller, and Father Bruce remained close friends. “Dear Jerry,” “Bruce Medaris wrote in October 1970, “as I told you last year, I have been able to release the remaining items of my collection….This should make it possible for you to complete the room that you have told me was being set up (in the University’s Special Collection). As I review the total of memorabilia that I have sent to the institute, I feel that perhaps all of it together might clearly illustrate the fact that one does not need either family or money to make success in this America. I really think that feeling needs to be preserved.” (Medaris, 1970)

The memorabilia included the desk that General Medaris sat behind as he directed America’s space program. This desk now resides in the Special Collections at the Evans Library. From behind this desk, General Medaris laid the foundation of the American space program. In a 1958 proposal, he called Project Horizon, Medaris envisioned a fleet of Saturn V rockets reaching the moon. On July 20, 1969, Medaris’ dream was realized when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the moon. It should not be forgotten that “during the crucial years of 1956 to 1960, when the space age began,” science writer Marsha Freeman observed, “they [the rocket scientists in Huntsville and at the Cape who built the Saturn V] worked under the guidance of Gen. John Bruce Medaris.” Freeman maintained that it was only just that General Medaris, “Father Bruce,” should be remembered as “the man who put America into space.” (Freeman, 1990, p. 14)

A Final Battle

In his last years, Medaris became embroiled in a final battle. His adversary was not Hitler’s Wehrmacht, Pentagon bureaucrats, or missile contractors but rather the Episcopal Church. Medaris was a man who played by the book. The Episcopal Church’s decision in 1974 to ordain women priests was too much for him. Noting that none of the Twelve Apostles had been a woman, Medaris declared, “that was the last straw on this camel’s back. What has happened in the Church in the last six years is a concerted effort by leadership to move doctrine into harmony with what people want to do. This is not a popularity contest. It is a church…. Women’s primary mission is to maintain beauty, gentleness and the spirit of love. It’s man business to confront danger, hostility and risk of a cruel world.” (Anonymous, 1979)

Times Change

Times change. On June 18, 1983, Sally Ride took her seat on the Space Shuttle Challenger (STS 7), on a launchpad that General Medaris had once commanded, and became the first American woman to be launched into space.* In 2016, Ann E. Dunwoody, a 1988 Florida Tech grad and the first woman in the U.S. military and uniformed services to reach the rank of four-star general, joined the Florida Institute of Technology Board of Trustees. One wonders what John Medaris would do if he were to meet General Dunwoody. I like to think that John Bruce Medaris, “Father Bruce,” who was a stickler for military etiquette and discipline, would have tucked his swagger stick under his arm, come to attention, and saluted his superior officer.

- *Three Florida Tech women graduates have served as astronauts: Sunita Williams (STS-116, STS-117), Joan Higginbotham (STS-116), and Kathryn Hire (STS-90). In August 2018, Sunita Williams was named to serve as an astronaut on CTS-1 mission of the Boeing CST-100 Starliner.

- Acknowledgment: I am indebted to Diane Newman, Special Collections Curator, Erin Mahaney, University Archivist, and Lisa Petrillo, Assistant University Archivist, at the John H. Evans Library, for their help in preparing this installment in the Secret History. The Evans Library Digital Collections contains an online collection of the Medaris Memorabilia that can be found at https://digcollections.lib.fit.edu/exhibits/show/the-medaris-collection-memorab

- Anonymous. (1972a). Keuper Scrapbooks Volume 24 January-July. Harry P. Weber University Archives of Florida Institute of Technology Special Collections, John H. Evans Library, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, FL.

- Anonymous. (1963, June 14). College Honors Gen. Medaris. The Daily Times.

- Anonymous. (1972b, February 17). Space Chapel Bill is Signed. New York Times.

- Anonymous. (1973 ). Keuper Scrapbooks Volume 28 June-September. Harry P. Weber University Archives of Florida Institute of Technology Special Collections, John H. Evans Library, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, FL.

- Anonymous. (1973/4). Keuper Scrapbooks Volume 29 September-March. Harry P. Weber University Archives of Florida Institute of Technology Special Collections, John H. Evans Library, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, FL.

- Anonymous. (1979). Space Race Pioneer Now Episcopal Priest. Reading Eagle. Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1955&dat=19790311&id=UPQhAAAAIBAJ&sjid=nKAFAAAAIBAJ&pg=5016,542938

- Copeland, D. H. (1963). Research and Renewal. The Living Church, 146, 7-8.

- Folkart, B. A. (1990, July 16). Maj. Gen. John Bruce [Medaris]; Head of Unmanned Space Unit. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-07-16-mn-135-story.html

- Freeman, M. (1990). Im Memoriam: Gen. John Bruce Medaris: The Man Who Put America into Space. 21st Century Science and Technology, 3(4), 14-16. Retrieved from http://wlym.com/archive/oakland/docs/1990Winter-TCS.pdf

- Gallagher, P. (1972, December 3). A Prayer for Apollo. Florida Today.

- Harris, A. (1989, March 10). Touchdown for America’ Pioneer Rocket Man. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1989/03/10/touchdown-for-americas-pioneer-rocket-man/a648f010-ade2-4ecb-9588-d6b1107142c0/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.35205849edf0

- Hearing Before the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences. (1971). S.J. Res. 42 and H.R. 11487 Convey Certain Lands in Brevard County, FLA. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office

- Hinson, S. (1975). Cured of Cancer, A General Turned Priest Uses His Faith to Try to Heal Others. Retrieved from https://people.com/archive/cured-of-cancer-a-general-turned-priest-uses-his-faith-to-try-to-heal-others-vol-4-no-2/

- Howell, E. (2018). Apollo 8: First Around the Moon. Spaceflight. Retrieved from https://www.space.com/17362-apollo-8.html

- Keuper, J. (1974, December 4) Letter. Harry P. Weber University Archives or Florida Institute of Technology Special Collections, John H. Evans Library, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, FL.

- Le Beau, B. F. (2003). The Atheist: Madalyn Murray O’Hair. New York: NYU Press.

- Medaris, J. B. (1970, October 1) Letter. Harry P. Weber University Archives or Florida Institute of Technology Special Collections, John H. Evans Library, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, FL.

- Noble, D. (1997). The Ascent of the Saints: Space Exploration. Interdisciplinary Encyclopedia of Religion & Science. Retrieved from http://inters.org/noble-religion-of-technology

- O’HAIR v. Paine, 312 F. Supp. 434 (W.D. Tex. 1969. (1969). Retrieved from https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/312/434/1468840/

- Patterson, G. (2000). Florida Institute of Technology: A College History. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing.