New Study Reports First Observations of a Star Swallowing a Planet

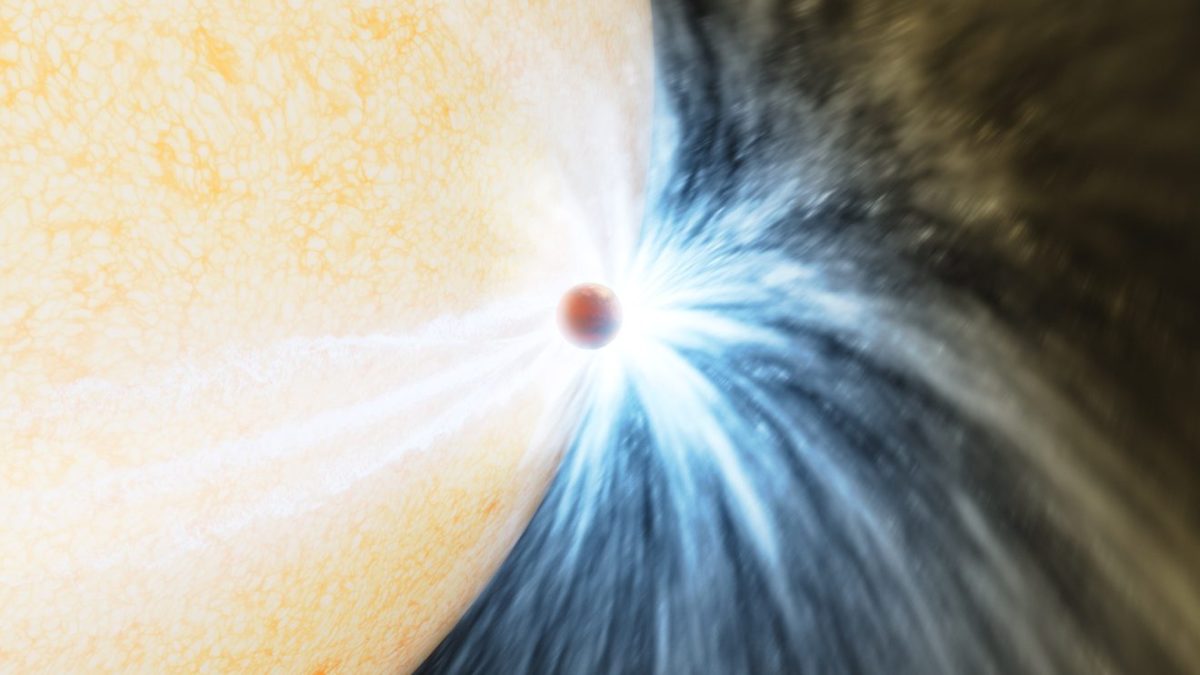

A new study involving Florida Tech assistant professor Luis Quiroga-Nuñez presents for the first time confirmed observations that a dying, expanding star has consumed a nearby planet.

The study, “An infrared transient from a star engulfing a planet,” was published this week as the cover story in the journal Nature. MIT researcher Kishalay De is the lead author, with contributions from Quiroga-Nuñez and researchers at MIT, Harvard, Caltech, Johns Hopkins, UC Berkley, the National Science Foundation’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Lab and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

“We were seeing the end-stage of the swallowing,” said lead author Kishalay De, a postdoc in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

The article reports an observation of a star merging with a gas-based exoplanet in May 2020. Though this sort of event may happen up to a few times every year within the Milky Way galaxy, this is the first time it has been observed. The incident took place in a star located approximately 12,000 light-years away, near the constellation Aquila.

When observing the skies for any brightness changes at the Zwicky Transient Facility, run at Caltech’s Palomar Observatory in California, astronomers spotted an outburst from a star that became more than 100 times brighter over 10 days before fading away. The white-hot flash was followed by a colder, longer-lasting signal, which led to De contacting the team of researchers to study what happened.

When the team further analyzed the data and paired it with measurements taken by NASA’s WISE space telescope, they confirmed what astronomers thought would happen at the end of a stellar cycle: the star expands as it dies, engulfing other planetary bodies around it and brightening on the outside in the process. This discovery also gives a preview of what will happen to our solar system and closest planets as the Sun dies. Astronomers expects that planets such as Mercury, Venus and Earth will be engulfed by the Sun in 4 billion to 5 billion years.

Specializing in radio astronomy, a subfield of astronomy that studies celestial objects at radio frequencies, Quiroga-Nuñez’s role in the research was to study the radio data that came from the area as the star engulfed the planet. During his research, he was intrigued by the idea of not knowing what exactly happened, the process of trying to figure it out via the explosion period, and what it means for the potential of planetary studies.

“This research is going towards bigger questions: How are planets formed and destroyed? Can similar organic material (as we have in the Earth) be formed in other planets? Is life possible outside of Earth? So far, we don’t know,” Quiroga-Nuñez said.

Observing a phenomenon, analyzing it, and confirming previous theories are major accomplishments, and so, too, is being part of a research group with a paper published in the Nature, Quiroga-Nuñez said. But landing the cover was a wonderful surprise.

“Publishing in Nature is very hard because you are competing with all other sciences, not only astronomy. You’re competing with a lot of astonishing research. The fact that Nature decided to publish the paper and then give us the cover means a lot for our research field,” he said.