Brevard Zoo’s Spider Monkey Complex welcomed three new faces this summer: Marcy and Finn, who were rescued after confiscation from the illegal pet trade in 2023, and a newborn named Sully. Since their arrival, researchers with Florida Tech’s Animal Cognitive Research Center have watched their integration, noting surprising pro-social behaviors.

The lab’s experimental testing was on hold for months while the new monkeys settled into the habitat. This pause allowed Darby Proctor, associate professor of psychology and Catherine Talbot, assistant professor of psychology, to spend more time observing the monkeys’ interactions. This fall, they plan to begin testing just how much the monkeys will support one another.

“We’re seeing hints that they have abilities that we wouldn’t expect them to have, and that’s really cool,” Proctor said.

Proctor explained that the spider monkeys are already known to be somewhat pro-social, which means they seem to care about the welfare of others. But an unexpected embrace between two monkeys – something Proctor and Talbot said is uncommon in primates – indicated that the species may be friendlier than they thought.

Marcy was just a few months old when she was introduced to Daisy, an older monkey in the habitat. Daisy attempted to walk up and embrace Marcy, who was too nervous and ran away. In response, Daisy sat down and turned her back towards Marcy, seemingly to give the young monkey time to calm down.

“Over the next hour, Marcy worked up enough courage to sort of approach her and run away and approach her and run away,” Proctor said.

Eventually, Marcy decided to touch Daisy on the shoulder. Daisy then turned around and opened her arms to the young monkey.

“Marcy came in for a big old hug, they started cuddling,” Proctor said.

When Daisy embraced Marcy, who was essentially a complete stranger, Proctor made note; greeting a new member with a hug is unusual for primates, she said.

The embrace mimics a human hug, but with a catch. Spider monkeys have a special scent gland in their armpits, which they sniff during the embrace. Talbot calls this a “pectoral sniff.”

“They kind of look like they’re sniffing one another’s armpits, presumably getting some additional chemical information from them,” Talbot said. “We don’t really know exactly what information they’re getting yet.”

The researchers have also seen the monkeys embrace when they’ve been away from each other for some time and in “a reconciliatory way” following an aggressive act, Talbot said.

Proctor witnessed this display of reconciliation from a monkey named Mateo.

Mateo arrived at Brevard Zoo in 2020 after he was confiscated from wildlife traffickers in Texas. He was the first confiscated monkey that Florida Tech helped rehome. His arrival paved the way for monkeys like Finn and Marcy; they were all victims of the illegal pet trade.

Mateo was essentially adopted by the group’s alpha male and is working to express his dominance, Proctor said. When Finn arrived, Mateo’s dominance startled him, which then startled Mateo, prompting some aggression towards the young monkey.

Less than one minute after the alpha male broke up the aggression, Proctor said Mateo went to embrace Finn.

“We’re seeing these monkeys work very quickly to repair their relationships, which again, it is pretty rare to see that level of reconciliation going on in this group of primates,” Proctor said.

The unexpected pro-social interaction compelled Proctor and Talbot to try to confirm their observations with experimental testing this fall.

“We’re seeing such cool things, and I can’t wait to continue getting that information more systematically so that we can definitively say it to the scientific world,” Talbot said.

One upcoming project is a cooperation task in which monkeys will work in partners to obtain a food reward. The process should help demonstrate who the monkeys work best with, Talbot said, whether that’s a best friend or someone in their family. Another project will assess the monkeys’ response to unequal outcomes, which reflects the likelihood of long-term cooperation.

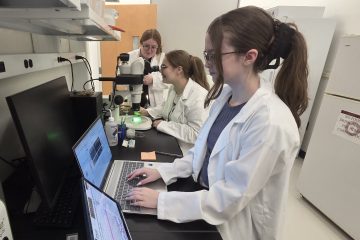

The researchers are also working with engineers and computer programmers to develop a computerized testing system to explore multiple aspects of the monkeys’ cognition. They plan to adapt computer games to understand elements such as the monkeys’ ability to recognize each other, ability to count, their inclination to gamble and their memory capabilities; ideally, Proctor and Talbot will be able to ask the monkeys any question they want.

“No one’s had the time and the space to sit down and really work with this species like we are getting to do here,” Proctor said. “We have to start at the beginning…but that means we’re going to find stuff out that no one else realizes about these animals.”