Blinking is a universal experience, but one that we rarely think about. We blink slower when we read and faster when we talk, and the average person blinks about 16,000 times a day.

We do it all the time, so what if we could better understand the condition of our brain based on just a blink? And what if we could monitor brain health without the use of large imaging machines, like CT scanners?

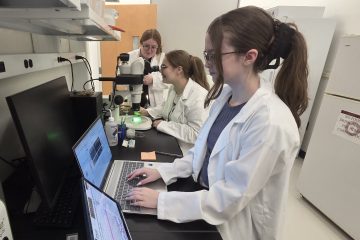

These are the questions Careesa Liu and Sujoy Ghosh Hajra, assistant professors in biomedical engineering and science, are trying to answer.

Liu and Ghosh Hajra recently published three articles on their research with blink-related oscillations (BROs), or the brainwave responses following spontaneous blinking—a new area of neuroscience and biomedical engineering Liu helped establish. Every time you blink, you lose complete visual input for about 100 milliseconds. When you reopen your eyes, your brain processes a brand-new image.

“Your brain then compares this new image with the last one stored in short-term memory,” Liu says. “Did anything change in the environment? Did any threats appear, like a tiger popping out of the corner of the eye?”

Analyzing this phenomenon can not only tell us information about blink-related processing in the brain, but it can also be used to gauge the underlying cognitive state of the brain.

In one study, Liu and Ghosh Hajra examined pilots as they completed various flight simulations. Using BRO responses to look at the pilots’ brainwaves when blinking, they were able to differentiate between an easy flight task and a harder flight task, as well as examine the effects of aging.

“Aging, especially in the early stages, can have a very subtle impact on brain function, and it’s relatively difficult to assess,” Liu says. “With this, what we’re able to see is that older pilots showed different patterns of blink-related processing relative to younger pilots when comparing between the harder and easier tasks.”

In the second study, they evaluated BRO responses when people completed a NASA-created task. The responses showed that the brain dynamically adapts and prepares for the upcoming blink to store relevant information when the person is engaged in a complex task, but not when they are doing a simple one.

“Our results show that the brain not only actively processes information with each blink, but it also dynamically adjusts how much brain power and effort it uses depending on what we are doing—all without us ever noticing it consciously,” Ghosh Hajra says.

Together, the findings from the two studies open a brand-new window into brain function, with applications in digital engineering, human-machine interaction, aviation safety, human factors, neuroergonomics, neurology, neuroscience and many others.

“The simplicity of the blink phenomenon as a brain function marker opens a world of opportunity irrespective of someone’s age, gender, race, socioeconomic background and other factors across clinical and non-clinical applications—creating a truly universal measurement of brain function,” Liu says.

In the third study, Liu and Ghosh Hajra examined soccer players who suffered subconcussions, which occur when they experience a hit to the head, but there are no clinical symptoms. Even though the players are not diagnosed with concussions, their brains are undergoing changes, which can be detected using BROs.

This information can also be used to monitor recovery and determine when an athlete is considered fit to play again.

“Blinking has traditionally been treated as a nuisance in brainwave measurements,” Ghosh Hajra says. “Previously, brainwave signals that contained blinks would have largely been thrown away, but there is actually very important and key information about what your brain is doing that is contained in these signals.”

Recent evidence indicates that this research can also be used in clinical settings to advance the diagnosis, monitoring and prognosis of certain diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease. BROs can help detect the underlying brain function changes and neurodegeneration that typically take place years before a patient shows disease symptoms, such as memory loss.

“The simplicity of the blink phenomenon as a brain function marker opens a world of opportunity irrespective of someone’s age, gender, race, socioeconomic background and other factors across clinical and non-clinical applications—creating a truly universal measurement of brain function.”

Careesa Liu, biomedical engineering and science assistant professor

Before working on BROs, Liu and Ghosh Hajra researched traumatic brain injuries caused by events such as a stroke, car accident or cardiac arrest. In these instances, to determine if the patient is still consciously aware, physicians typically use the Glasgow Coma Scale, which requires them to produce specific behaviors in response to commands, like squeezing a hand or closing and opening their eyes.

Liu says the problem with that approach, however, is that patients may be consciously aware and can understand what a physician is asking them to do, but they cannot produce the behaviors due to the nature of their brain injury.

“As a result, a lot of them end up being misdiagnosed,” she says. “Studies have actually shown that as many as 41%, so almost one in every two patients, who are diagnosed to be in a vegetative state are actually not.”

Alternatively, BRO responses allow physicians to look directly at the brain to extract measures of consciousness, as it looks at key regions of the brain that help drive our consciousness.

BRO responses allow us to measure the function of these regions directly, using the simple activity of blinking instead of requiring the patient to produce specific behaviors.

Analyzing BROs also provides a more cost-effective and easier way to monitor brain health in comparison to large-scale machines like CT and MRI scanners, as those require patients to process sensory information that they may not be able to.

Moving forward, Liu and Ghosh Hajra plan to analyze BRO responses in other scenarios, such as when a person is driving a car, as well as collaborate with other Florida Tech researchers to continue analyzing concussions and other clinical disorders, like autism.

Looking into the future, they envision a world where patients have a tool they can access every day to get a quick measurement of how their brain is doing.

“To get to that future, we need to demonstrate the application in all of these different domains, whether it’s clinical disorders and how we help people get better after a devastating injury, all the way to the other side of it with hyperfunction—to help aviators or astronauts perform at their best,” Ghosh Hajra says.

In parallel with showcasing the many applications of BROs, they are also working on engineering portable, user-friendly hardware so patients can check their brain function at home.

“Ultimately, where this research is headed is developing technologies that we can use in the home. So, when you wake up in the morning, you can put it on and see, ‘How’s my brain doing today?’” Liu says. “Like a smartwatch for the brain.”

This piece was featured in the spring 2024 edition of Florida Tech Magazine.