Sense and Sustainability

In a world fraught with environmental and economic challenges, graduates with sustainability skills are in high demand.

When Christian Foster arrived at Florida Tech in 2018, the Rochester, New York, native planned to major in aerospace engineering. That remained his thinking until midway through his sophomore year, when his career aspirations changed.

He opted to major in sustainability.

“I felt like I had a lot more to contribute to this field,” Foster says, “and I found out how uniquely awesome the program was here.”

With an unprecedented surge in sustainability-related jobs in the U.S. and beyond, Foster, who graduates in December 2023, and future students of Florida Tech’s unique, STEM-based sustainability program will have no shortage of opportunities.

LinkedIn featured 133,000 sustainability jobs in early December 2022, with opportunities ranging from corporate social responsibility and environmental, social and governance (ESG) executives to interns, technicians and specialists.

While there are certainly fields that have more openings—at the time, there were nearly 920,000 nursing jobs on LinkedIn, for example—the rising demand for sustainability professionals is a relatively new trend that has gathered momentum following the COVID-19 pandemic. It will put successful sustainability programs like Florida Tech’s in the spotlight, and in greater demand.

“What’s happening in the last five to 10 years is that the larger corporations, and increasingly the mid-scale corporations, are leaning in to sustainability and resilience,” says Ken Lindeman, an ocean engineering and marine sciences professor who built Florida Tech’s sustainability program.

Why are more businesses leaning in to sustainability? What is the view from those within the field? And what is motivating students to seek this vocation?

‘The Great Expansion’

“Business leaders are facing an intense landscape, as climate-related disasters occur with startlingly high frequency and intensity. The pressure to act on sustainability from all stakeholders is greater than it has ever been,” according to “Climate Leadership in the 11th Hour,” the 2021 edition of the decennial United Nations Global Compact – Accenture CEO Study on Sustainability.

Another report, the State of the Profession 2022 from GreenBiz, put it this way: “This is indeed an unprecedented moment for the profession, one that may come to be referred to as ‘The Great Expansion.’”

But the rise in sustainability opportunities is about more, and runs deeper, than jittery companies protecting their bottom lines with new recycling programs or a newly hired resilience coordinator. The rise in sustainability-related jobs is societal and even generational, as well as economic.

For starters, it is increasingly difficult for people to ignore climate change. Yes, there are still doubters, but more people in the U.S. and beyond are realizing how inaction could condemn future generations to many avoidable challenges in a vastly changed climate.

“Nothing gathers the attention of people like an impending crisis,” says economist and Nathan M. Bisk College of Business professor Michael Slotkin. “People procrastinate, but this has permeated a wider share of people who believe, ‘This is real. We have to do something.’”

The COVID-19 pandemic played a role in this, too, according to the Accenture report, which is based on insights from more than 1,200 CEOs across 21 industries and 113 countries. Nearly four in five CEOs (79%) say that the pandemic has highlighted the need to transition to more sustainable business models.

George Oliver, chairman and CEO of Johnson Controls, the global conglomerate that produces electronics and HVAC equipment, told Accenture, “I would have predicted that a crisis like COVID would have slammed the brakes on anything other than conventional bottom-line thinking—and the fact that it did the exact opposite is extraordinary. It has accelerated the trajectory of sustainability.”

Another factor is the workforce itself and its influence, Slotkin says. Younger workers have not been forged by economic depressions and are not necessarily motivated only by financial gain and the security that could bring.

“They want to have a purpose,” Slotkin says. “If it becomes more about a purpose than a paycheck, young workers are going to check out unless they view their companies as trying to do something in a particular area. They want to believe in what they are doing and want the company to take a stand.”

Count Nicole Barnett ’21, who earned a bachelor’s degree in sustainability studies, in that group. She recalls sitting in a sustainability class with her roommate and being reminded of how pressing these issues—and the need to do something about them—are.

“Outside of class, we were still talking about it,” she says. “It definitely clicked with me that that is what I needed to be doing.”

And as awareness of companies’ benefitting from climate-related decisions grows, others on the fence may be opting in.

“Companies now understand that if they do this a little bit or try, they can obtain competitive advantages, improve community relations and improve risk management,” Lindeman says. “And there’s data that show they recruit and retain better employees.”

The third element of the surge is growing awareness in the business world and beyond that the government, despite recent high-profile actions such as the Inflation Reduction Act, will need help.

“If you feel like you are getting stasis from your public authorities, you will see the nation’s attention moves toward businesses and people that work there,” Slotkin says.

On the Job

If Zachary Eichholz ’16, ’19 M.S., is getting the nation’s attention, he’s too busy to see it.

The 29-year-old deputy community and economic development director and sustainability manager for the City of Cape Canaveral has known only the sustainability profession since he graduated from Florida Tech in 2019 toting a bachelor’s degree in sustainability studies and a master’s degree in interdisciplinary sciences. It wasn’t hard to find motivation.

“I don’t think it’s naïve to say that this is our generation’s moonshot. Younger individuals, I believe, are a little more adaptable than our predecessors just because of the sheer number of things that have happened across the world in the 21st century,” he says, naming two once-in-a-generation economic crises, the global COVID-19 pandemic and the horrors of 9/11 that started the century.

I don’t think it’s naïve to say that [sustainability action] is our generation’s moonshot.”

Zachary Eichholz ’16, ’19 M.S.

“Climate change has been creeping up in the back that entire time,” he says. “We are the generation that sees the challenges head on, and this has galvanized us, on the flip side, to react and be proactive to remediate these issues. We want to have a livable world, too, that we’ve inherited.”

As with Foster and Barnett, Eichholz came to Florida Tech with a different path in mind. Though he was aware of environmental issues and started with plans to minor in sustainability, the Florida native was fascinated by hurricanes and fully planned to study them and earn a degree in meteorology.

Amid all of this, Eichholz couldn’t help but see that what he called “the green path toward sustainability” would offer a more fulfilling career while still allowing him to explore some facets of meteorology. When Florida Tech launched its sustainability major program in fall 2013, he was all in.

With a sustainability internship for the City of Satellite Beach that Lindeman helped arrange—as he would continue to do at multiple cities across Brevard County for students, including Barnett—Eichholz saw the potential of this profession.

“I could kind of see early on that cities, counties, private companies would probably start to embrace this stuff as more and more issues came about that needed to be addressed,” he says. “You could tell there would be a lot of opportunities, and it would be quite expansive.”

Barnett entered Florida Tech as an environmental science major but was open to other opportunities. She hadn’t heard of sustainability studies, but when she learned more about it and its mix of STEM and business courses, the fit was there and she switched majors.

“‘This is kind of exactly what I am interested in,’” she remembers thinking. So, she changed her major. “I jumped on this train, and I love it.”

Starting in the second semester of her junior year, she interned for the City of Palm Bay, a period she called “the biggest catapult in my educational career.”

At Brevard County’s largest city, she was instrumental in the development of the city’s first sustainability action plan, working closely with city staff and the Sustainability Advisory Board.

That process allowed her to work in public policy and understand how sustainability and related practices function in a municipal setting, both critical skills for her future employment. And the report itself, which was also her senior capstone project, played a big role in that first job, too.

After wading into the job market with limited responses, Barnett posted her Palm Bay project on LinkedIn. Almost immediately, she got a message from EXP, a multinational firm providing engineering and design services. A short time later, she started an internship there, and by August 2021, she was a full-time municipal sustainability planner. She has now also earned the credential EN SVP: Envision Sustainability Professional.

At EXP, she provides sustainability input on projects along with input from engineering, design and other areas, including a Miami project to develop building materials that will repel airborne salt from ocean mist and not heat up in that famous Florida sun. She also works on credentialing buildings to become LEED certified.

“Every project has some sort of resiliency or sustainability component,” she says. “Net-zero [energy], like our alumni center on campus—all of these things Florida Tech has that I’ve been exposed to help me be familiar with terms of industry.”

In his role, Eichholz has helped take Cape Canaveral forward in substantial ways. A leading example is the city’s community center. Opened in September 2022, the nearly 25,000-square-foot facility was designed with a modern, window-heavy sensibility.

One of its most exciting features, spearheaded by Eichholz, may not be noticed by most visitors: a rooftop solar array, the city’s first. Composed of 72 panels, the 48-kilowatt array is estimated to save the city over $242,500 in energy costs and abate 1,325 tons of carbon dioxide emissions over its 25-year lifespan.

Beyond that, Eichholz and the city are planning to make the building a reliance hub. It will be a community center most times, with its gym, multipurpose room and so forth. But when an emergency strikes, because of the power that will be produced by the array—which is designed to withstand winds of up to 160 mph—it can function as a hub for the distribution of food, water and other resources.

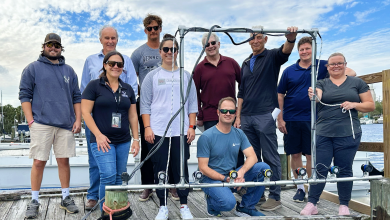

Eichholz has also led efforts to install a network of remote sensor sites across the city to measure weather data and tide levels.

“There is a lot of data on climate change, but when you get down to hyperlocal level, it’s difficult to pinpoint exact issues. So, we are planning for and mitigating potential threats like urban flooding,” he says, “and building our understanding of its influence on stormwater below ground. For example, ‘Why did one street flood but not another?’”

The network has allowed city officials to see events as they happen and, equally important, respond in real time in a way they haven’t been able to before, Eichholz says. It also provides useful data to use when designing and engineering new buildings.

This has resonated with many residents, who have expressed themselves during the city’s ongoing development of its sustainability and resiliency plan, the Cape Canaveral 2063 Program, which informs the city’s broader sustainability and resilience program.

“It is very enlightening, empowering and validating to see residents say, ‘I think we need some changes. I want to live here, have a city that is livable, viable and safe—what are you going to do?’” he says.

The city has also recently formed a Resilience Division within the Community and Economic Development Department. To help run the department, the city hired Alexis Miller ’15, ’19 M.S., as resilience engineering services manager.

Challenges Ahead

With about 20% of Florida coastal municipalities now featuring sustainability and/or resilience staff, and likely similar or smaller percentages across the country, Lindeman says local government should be a landing spot for many new workers in the field.

“In urban areas in Florida, the city planners and city managers have to deal with the reality on the ground, the impacts of now sunny-day high tides that are flooding streets in multiple areas and many other issues further below the surface,” he says. “These positions are needed.”

Barnett agrees.

“At the local government level, I don’t think those positions will be removed from now on. Resiliency officers, sustainability planners will be embedded, hopefully, in every municipality.”

Foster is encouraged by what he sees in the job market.

“We are on the precipice. We have to do something, and companies want to be the ones that did something,” he says.

We are on the precipice. We have to do something, and companies want to be the ones that did something.”

Christian Foster, Sustainability Studies Student

He is interested in institutional sustainability, and his capstone project is to carry out portions of Florida Tech’s STARS certification efforts. STARS is a comprehensive sustainability rating system for colleges and universities that addresses the environmental, social and economic dimensions of sustainability.

“Everyone here seems to be very forward-thinking. I think everyone here is aligned very well,” Foster says. “It’s a great experience for me because I would like to work in the private or public sector, making legislation, working as a sustainability officer for a company—instead of making innovations, implementing them.”

He added about the university’s sustainability program, “I can confidently say I haven’t met anyone in this program who isn’t doing something related to what they want to do in the workforce.”

One way to boost sustainability traction is to monetize the process, which Barnett describes as, “making it attractive to get things done but turning the change into a profitable and attractive investment for industry.”

That approach, such as giving builders credits for making their structures energy efficient, can help normalize sustainability practices, Lindeman says.

“The way you do that is by monetizing the good and creating jobs that have an implicit, if not explicit, role in monetizing the good,” he says.

Are there downsides to being sustainability professionals and being knee-deep in forecasts of rising seas, rampant high temperatures, violent storms and the like?

The phenomenon of climate anxiety is real, Eichholz says.

“It can be a lot,” he says. “You fight that with a map of how many new solar arrays you can put up across the city, how much emissions and energy does it save?”

And they draw encouragement from, what all involved hope is, growing public support.

“By basically catalyzing your efforts into action, doing projects and initiatives on the ground no matter how small or what scale of government or private company you’re in, making a difference day in and day out—that is a way to make an actual difference and keep your own mindset positive and strong,” Eichholz says.

“You are kind of, we don’t say, ‘killing two birds with one stone.’ We say, ‘releasing two birds with one stone.’ That’s the way you fight the existential dread.”

This piece was featured in the winter 2023 edition of Florida Tech Magazine.